The news is grim: According to a report compiled by hundreds of scientists from 50 countries, Earth is losing species faster than at any other time in human history. Thanks to climate change, coastal development and the impacts of activities such as logging, farming and fishing, roughly 1 million plants and animals are facing extinction.

The UN report calls for rapid action at every level, from local to global, to conserve nature and use it sustainably. And here’s some potential good news: Many ecosystems now at risk can provide valuable services if they are protected.

I know from my research on coastal habitats that the biggest obstacle to investing in natural infrastructure, such as wetlands and reefs, often is that experts have not figured out how to value the protection that these habitats provide in economic terms. But a new report that I co-authored, published by the U.S. Geological Survey’s Coastal Hazards Program, solves that problem for one of our planet’s most biodiverse ecosystems: coral reefs.

This report shows that coral reefs in U.S. waters, from Florida and the Caribbean to Hawaii and Guam, provide our country with more than US$1.8 billion dollars in flood protection benefits every year. They reduce direct flood damages to public and private property worth more than $800 million annually, and help avert other costs to lives and livelihoods worth an additional $1 billion. Rigorously valuing reef benefits in this way is the first step toward mobilizing resources to protect them.

Breaking waves and blocking floods

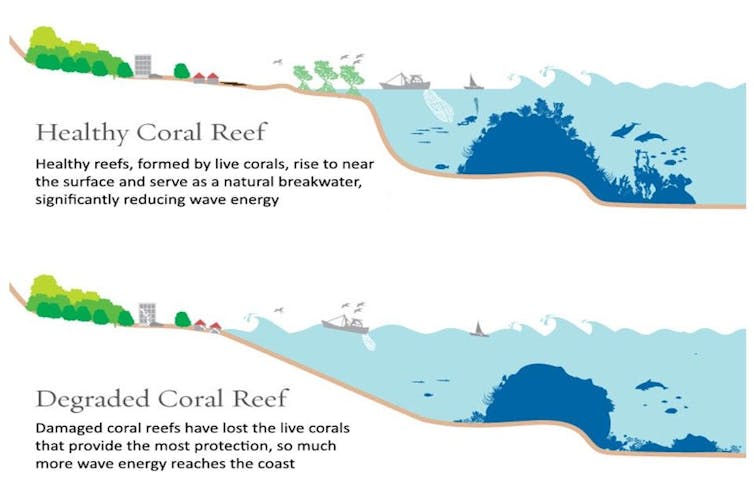

Reefs act just like submerged breakwaters. They “break” waves and drain away their energy offshore, before it floods coastal properties and communities. This is an enormously valuable function. In 2017, tropical storms alone did over $265 billion in damage across the nation.

Manmade defenses, such as sea walls, can damage adjoining habitats and harm species that rely on them. In contrast, healthy reefs enhance their surroundings by protecting shorelines and supporting fisheries and recreation, from diving to surfing.

The flood protection benefits that reefs provide across the U.S. are similar to those in more than 60 other nations. As I estimated with colleagues in a separate study, the global cost of storm damage to the world’s coastlines would double without reefs.

Pinpointing local flood protection value

Our estimate of the value of flood protection from reefs applies state-of-the-art tools that engineers and insurers use to assess flood risks and benefits.

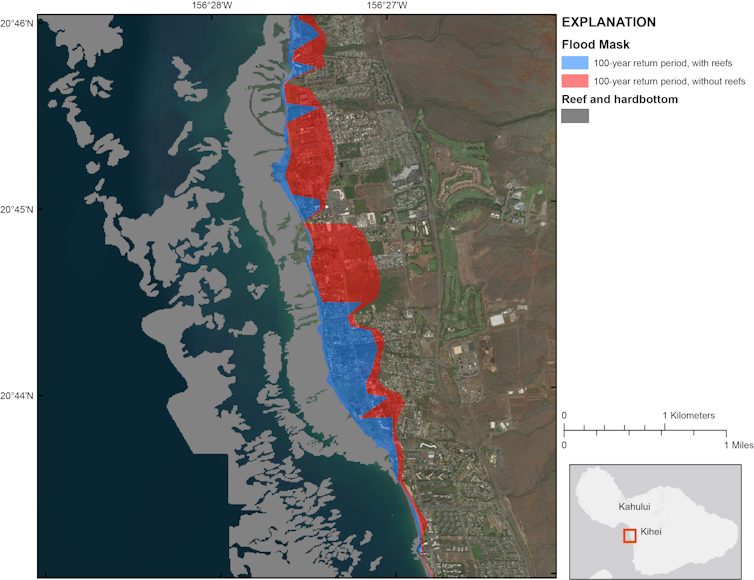

Using a model and more than 60 years of hourly wave data for all U.S. states and territories with reefs – a total area of over 1,900 miles – we developed flood risk maps projecting the extent and depth of flooding that would occur across many storms, both regular and catastrophic, with reefs present and then without them. We calculated these values in grid cells that measured just 100 square meters, or about 1,000 square feet – the footprint of a small house.

Then we overlaid these flood risk maps on the latest information from the U.S. Census Bureau and the Federal Emergency Management Agency to identify people and properties at risk – and benefiting from the presence of reefs – in each location.

With this level of detail, we now can identify not just total benefits provided by reefs, but who receives them. For example, Florida receives more than $675 million in annual flood protection from reefs, and Puerto Rico gets $183 million in protection yearly. In Honolulu alone, we found that reefs provide more than $435 million in protection from a catastrophic 1-in-50-year storm – an event large enough that it would be expected to occur only once in a 50-year period.

It is well known that coral reefs are under heavy stress from climate change, which is warming oceans, causing coral bleaching. Pollution and overfishing are also doing serious damage. As the UN report on biodiversity loss notes, Earth has lost approximately half of its live coral reef cover since the 1870s. And that trend leaves 100-300 million people in coastal areas at increased risk due to loss of coastal habitat protection.

Investing in natural defenses

How can our valuation study inform coral reef protection?

First, it buttresses the case for using disaster recovery funding to help natural coastal defenses recover. After Hurricane Sandy in 2012, only about 1% of recovery funding went toward rebuilding natural resilience, despite subsequent research showing that marshes in the Northeast can reduce flood damages by some 16% annually.

More than $100 billion has been appropriated to recover from hurricanes Harvey, Maria and Irma; it would make economic sense to spend some of these funds on rebuilding reefs. In a promising move, the Federal Emergency Management Agency has created opportunities to include ecosystem services such as flood protection and fishery production in official benefit to cost analysis calculations to support flood mitigation funding.

Second, the insurance industry has an important role to play in offering incentives and supporting investments in nature-based defenses for risk reduction. Insurers are starting to consider habitats in industry risk models and to create opportunities to insure nature. Thus reefs could be re-built if they are damaged in storms or even restored now based on their proven flood protection (i.e., premium saving) benefits.

Third, federal agencies have incentives to invest in reefs as protection for critical infrastructure. Reefs defend military bases located along tropical coastlines, as well as shore-hugging roads that are the lifeblood of many economies from Hawaii to Florida and Puerto Rico.

Through its Engineering With Nature initiative, the Army Corps of Engineers is making more use of natural solutions to minimize flood risks. And the U.S. Department of Transportation is analyzing ways to protect coastal highways with nature-based solutions, such as marsh restoration. These programs are a start in the right direction.

The new UN report clearly identifies key threats to species and ecosystems. Our work provides rigorous social and economic values quantifying what is at stake. My co-authors and I hope it creates new incentives to invest in coral reef conservation and restoration and to build coastal resilience.

![]()

Michael Beck, Research professor, University of California, Santa Cruz

This article was originally published in The Conversation. Read the original.