Waves of disaster have earned Louisiana a reputation as the place to watch for how climate change will impact coastal areas. Hurricane Ida was merely a punctuation mark in a series of devastating tropical cyclones, tragic inland floods, epic oil spills and deadly epidemics.

Despite these all-too-frequent catastrophes, many residents of Louisiana’s vulnerable coastal areas remain firmly committed to rebuilding after each disaster. The powerful pulls of family, faith, traditional foods, local music, culture and landscapes create a strong attachment.

Native Americans, African Americans, Acadians, Isleños and Vietnamese populate the coastal region, living in narrow settlements along the bayous and natural levees that stand a few feet above the backwater swamps and marshes. Many come from a history of traumatic displacement from their traditional homelands. They adapted to the local environment, became skilled shrimpers, fishers and oyster farmers and sunk deep roots.

In coastal Louisiana, people often live their entire lives near where they were born. Yet they have also moved, incrementally “up the bayou” – away from the Gulf of Mexico – over the decades in order to survive in a perilous place. Each major storm prompts a few more departures that contribute to a slow trickle of recovery-weary residents.

As the state tries to cope with repeat catastrophes, it is figuring out how to manage an ongoing crisis – the slow-motion loss of these southern wetlands and barrier islands. They provide valuable natural storm protection. But the state’s solutions may end up harming the communities that live there and endangering the unique cultures that define the Louisiana coast.

As a historical geographer living in Louisiana, I study these areas and recently published a book on Louisiana’s land-loss crisis. My research documents how these rural areas are being asked to adapt to save cities and industries, and how that’s affecting their cultures.

The downside to wetlands restoration

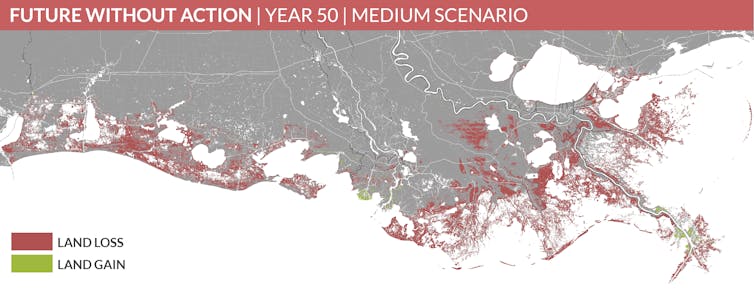

The state’s coastal margins have been disappearing at the rate of about 23 square miles per year. That’s due in part to flood protection levees that redirected water-borne sediment away from the Mississippi River Delta. This sediment once seasonally rejuvenated the river’s floodplain, backswamps and marshes during spring flooding. Now, it’s channeled between high levees, so all that material is carried far offshore.

Without regular replenishment, the delta sinks. Navigation canals dug for oil and gas development have contributed to saltwater intrusion and erosion, furthering land loss. Pumping oil and gas also accelerates the land’s subsidence.

The gradual rise of the water level in the Gulf of Mexico as the climate warms, combined with these other processes, exposes Louisiana to the highest rates of relative sea level rise in the U.S. That makes the low-lying coastal parishes more susceptible to erosion and storm surge flooding like Ida’s.

Fixing one problem, creating another

To offset this slow-moving disaster, the state has launched an ambitious program to fortify the coast and restore wetlands and barrier islands.

The plan includes structures to divert Mississippi River water and sediment into the marshes again. But those freshwater diversions bring another problem: They can change the water chemistry and add sediment, affecting the oysters, shrimp, crabs and fish that residents depend on.

The state’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, which is directing this gargantuan effort, is attentive to protecting the major industries and largest cities, restoring critical coastal habitats and ecological functions, and assisting coastal residents. Toward these ends it has spent millions of dollars studying the geology, hydrology and ecology of the region. And it intends to spend billions on its projects, which would create multiple layers of defense such as restored wetlands and barrier islands, along with levees.

Its regularly updated plans note that local culture matters as well. Yet, it hasn’t measured the social and cultural processes at work or modeled their future. Planners have offered no designs for protecting and restoring cultures that will be disrupted by either land loss or the projects on the drawing boards.

Cultures at risk

Distinctive ethnic and culture groups have persisted here despite living amid the waves of calamity that wash over their homes. Our studies explain how locally based practices have enabled them to rebound, rebuild and recover after hurricanes, river floods, epidemics and oil spills. Social scientists refer to these as inherent or informal resilience.

Long before the arrival of Civil Defense, FEMA or other government-organized response efforts, residents deployed these practices, enabling people reeling from a hurricane to begin rescuing, sheltering and feeding neighbors and repairing housing and workplaces.

The state’s restoration plans neglect these fundamental cultural skills.

The plan also allows for “voluntary acquisition” of homes of those who live beyond the structural protections and wish to depart. Yet, there has been no meaningful discussion, study or planning for assisted resettlement of at-risk communities by the agency in charge of coastal restoration. Another agency has worked for several years to assist the largely Native American community of Isle de Jean Charles to begin an inland move. There is no comparable effort for other communities within the master plan.

Buyouts may enable some families to escape a precarious situation. But without community-wide resettlement assistance, it will inevitably contribute to community fragmentation and cultural dissolution as residents drift apart.

As cultural communities erode due to departures caused by massive storms and other disasters, the state is abetting, unintentionally, the disintegration of the coastal region’s distinctive and highly valued cultures.

A warning to other coastal areas

Louisiana’s landscape offers a preview of what might be expected in other locations facing sea level rise and seeking protection behind fixed dikes or levees.

These barriers tend to disrupt local environments that resource-based economies such as fishing depend on. They also contribute to a “levee effect” – the creation of a false sense of security that exposes coastal residents to severe impacts when a storm exceeds the levee’s design limits.

With each successive storm, recovery funds will go into repairing damaged rigid coastal protection systems, like the US$14 billion to repair the New Orleans levees after Hurricane Katrina and the untabulated damage to restoration projects caused by Ida. That means less money available to address the needs of threatened cultural communities.

Designing protection systems that incorporate informal resilience, such as community-directed resettlement planning, or that integrate with existing social networks can protect both coastal cultures and inland populations. And when conditions become untenable, as some Louisiana settlements are discovering, the state’s investments may have to go beyond individual buyouts to help communities plan a safer future together.

Craig E. Colten, Professor Emeritus of Geography, Louisiana State University

This article was originally published in The Conversation. Read the original.