"As leading companies set water commitments reflecting their fair share, others have taken note"

The World Resources Institute’s Water Program empowers companies to reduce business risks related to water, driving business growth and building resilience while contributing to solving water challenges and advancing the Sustainable Development Goals.

The private sector is increasingly realising that water risks can be a threat to businesses; the World Resources Institute (WRI) provides guidance to companies on water stewardship initiatives so they can advance sustainable water management and increase their resilience to water and climate shocks. For agribusiness such as Cargill, this meant partnering with WRI to look beyond direct operations and into their agriculture supply chain, setting water targets with the help of WRI’s Aqueduct data tools. We speak to Sara Walker, WRI’s Director of Corporate Water Engagement, about corporate water stewardship and the institute’s work with companies to build resilience across the entire value chain and improve collective water security.

Could you tell us briefly about your career path and your current role in the World Resources Institute?

I received my bachelor’s in Environmental Studies and Psychology from Dickinson College. In my senior year, I participated in a watershed-based integrated field semester exploring and comparing the scientific, political, and social variables in the Chesapeake Bay and Lower Mississippi River watersheds. I think this experience launched me into the water space.

After undergrad, I worked as an environmental management staffer at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Chesapeake Bay Program Office supporting the multi-stakeholder partnership’s efforts around nutrient pollution. WRI was a dream organization for me, so when it was time to move on from this position, I applied to a couple of positions before landing with the water quality team as a Research Analyst in 2009. At the time, WRI had a significant workstream on market-based mechanisms for eliminating eutrophication, including in the Chesapeake Bay watershed so it was a natural fit.

Over the past 13 years at WRI, my role has grown and evolved to include more international work in the water quality space, additional water challenges, and a focus on agriculture and food security which included the development of WRI’s Aqueduct Food tool for analysing water-related risks to agricultural production globally. Now in my current role as the Director of Corporate Water Engagement, I work closely with the private sector on water stewardship by providing thought leadership, working one on one with companies on water risk assessments and target-setting efforts, and convening leading companies and others who join our Aqueduct Alliance to gain strategic guidance and help to advance water stewardship best practices.

Large companies are increasingly making water stewardship commitments. What are the major drivers behind these pledges?

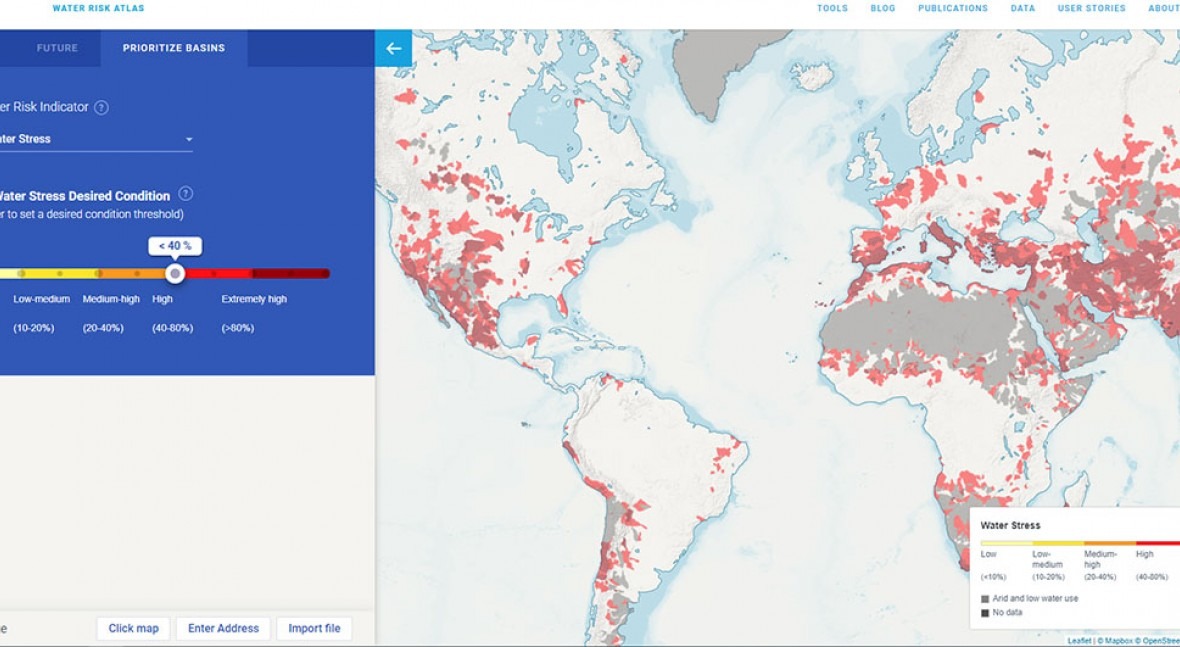

Yes, it’s been fantastic to observe the growing number of companies that are setting really ambitious and contextual water targets. Many companies use WRI’s Aqueduct tools to assess their water risks, and this is foundational to starting on a water stewardship journey. If they have facilities in an area that is currently – or projected to be – at high risk of water stress, for example, that creates an impetus to act now to ensure they can continue to operate. In these high risk areas, companies can then assess the change required to ensure sustainable levels of water use. Well-crafted commitments that effectively address these risks can ensure business resilience.

Many companies use WRI’s Aqueduct tools to assess water risks, and this is really foundational to starting a water stewardship journey

As leading companies have set commitments reflecting their fair share (or more!), others have definitely taken note. There’s also a growing focus on looking beyond direct operations to the entire value chain – as a company’s most significant water impacts and dependencies may be upstream or downstream. This is especially true for the food and beverage sector given agriculture is a major water user and can have significant water quality impacts. Cargill, for example, recognized this and partnered with us to set contextual water targets that would reflect sustainable water management by 2030 for their direct operations and agricultural supply chain.

The magnitude and complexity of the value chain of a company like Cargill is daunting; how can WRI’s tools inform water risks and help set priorities and targets?

It can definitely seem daunting at first! Cargill has more than 1,000 direct operations in 70 countries, and its agricultural supply chain includes more than 6,500 watersheds. Following WRI’s guidance on Setting Enterprise Water Targets, we strove to balance pragmatism with a scientifically robust approach. Global tools and datasets are key here. We leveraged WRI’s Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas that provide globally comparable data on water risks to prioritize hot spots – basins whose risk scores exceeded our desired condition thresholds - where targets should be set.

There is a growing focus on looking beyond the company’s direct operations to the entire value chain – upstream or downstream

Location information is important, but often companies don’t have full traceability of their agricultural supply chains. They may know they source wheat from France but do not have more specific information on the geography. So we also leveraged Aqueduct Food’s global, geospatial cropland data to help us understand water risks specific to where crops sourced by Cargill were likely to be grown using whatever level of location data Cargill provided.

By layering in where Cargill can drive change, we were able to identify priority watersheds for target setting that represent a fraction of the total possible watersheds, and which reflect where change is really needed and possible.

We’ve recently updated our Aqueduct suite of tools to automate much of this process for our private sector users to hopefully make the process even less daunting. Users can now assess desired conditions and changes required for every basin in which they have a footprint, and they can do water risk assessments for their agricultural supply chains with basic information about what crops are sourced and from where. These enhancements equip companies to set meaningful targets across their operations and supply chains.

Do you see this kind of approach that looks at water risks beyond direct operations and into the value chain expanding to other sectors?

Yes, absolutely. The Setting Enterprise Water Targets guidance is designed to be flexible across sectors and the value chain, so it can be applied in a variety of contexts.

The Setting Enterprise Water Targets guidance is flexible across sectors and the value chain, to be applied in a variety of contexts

We have been working with a consumer goods company on setting targets that will address downstream water risks related to the consumer use of their products. And hopefully, as more companies share details on how they adapted this guidance to meet their needs, we’ll be able to facilitate shared learning across and within sectors so the process isn’t so daunting for everyone.

Taking a value chain approach to setting targets will also be required by the forthcoming Science Based Targets for Nature guidance and water-specific methods. It is expanding to other sectors, and it should be considered best practice.

How could companies quantify the cost of actions to improve water management in their supply chain, such as changes in suppliers’ agricultural practices in the case of agribusinesses?

To meet these ambitious targets, significant investments will certainly be needed. By taking a rigorous approach to prioritizing hot spots, companies can ensure they’re also prioritizing funding in the areas that need it most. In Achieving Abundance, we estimated that achieving sustainable water management (i.e., SDG 6) – addressing scarcity, access to drinking water, access to sanitation, and water pollution – requires an annual cost of more than $1 trillion through 2030. Costs for specific interventions vary widely across the globe, but this resource provides a methodological framework for the private sector to calculate costs for any given location. Companies must factor these costs into their operating budgets to ensure they will be able to act on the commitments they set.

The water-energy-food nexus is complicated, and I see a great need to help companies and other decision makers navigate these dynamics

“Addressing water challenges in the agricultural supply chain can help improve farmer livelihoods, reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and improve resilience”. To what extent can addressing water risks take into account the links with food and energy security, and overall environmental health?

Water is essential for food production. We cannot grow crops without it, so we cannot have food security without water security. Likewise, farmer livelihoods are therefore also dependent on water security. As companies and other decision makers think about actions they can take to address water risks or reduce GHG emissions or improve soil health, there are massive gains to be made for nature if we can consider the co-benefits and trade-offs of any given intervention.

For example, if solar panels are provided to farmers as a free and green electricity source for groundwater pumping, this may be good for the climate, but if there’s no disincentive to pump or incentive to limit how much is withdrawn, we could see depleted groundwater tables.

On the other hand, agricultural practices like cover crops reduce the need for fertilizer and sequester carbon which is good for water quality, good for the climate, good for the soil, and ultimately good for the farmer through improved yields. The water-energy-food nexus is complicated, and I see a great need to help companies and other decision makers better navigate these dynamics for more effective decision making.

What role do you see for corporate water stewardship efforts in local contexts where there may be significant governance issues and competing water users?

The private sector can – and should – consider their sphere of influence and push for public policies that will improve governance

Governance is so important. While setting individual corporate commitments is necessary and the first step within their sphere of control, many of the water challenges in many locations are shared with other stakeholders in the basin. A single company meeting its own commitment is not likely to solve the basin-wide issue. This is where stakeholder engagement and collective action come in.

Setting contextual water targets calls for an understanding of not just the water challenges in any given basin but also the social, governance, and economic conditions. Interventions will vary depending on the local context across these variables. Ideally, stakeholders across the basin would convene around a common goal and allocation approach to ensure everyone is doing their fair share. In reality, this is time-intensive work that requires a local presence which isn’t always possible, particularly when tackling these issues up and down global value chains.

But as more and more companies reach this mature stage of their water stewardship journeys, this challenge is being addressed through WRI-supported efforts like the Water Resilience Coalition which is a CEO-led effort aiming to alleviate water stress through collective action.

In addition, the private sector can – and should – consider their sphere of influence and push for public policies that will improve governance and help achieve sustainable and equitable water resources management.