There are times when the solution to a specific problem becomes a revolution, although not necessarily a positive one.

This is the case with the invention of the automobile in the nineteenth century, partly in response to the transport needs of a world in midst of an industrial era, and partly to address a much more mundane cause: horse poop. Yes, that’s right.

Let’s take a look at how I reached this simplistic point by taking a look at history.

Animals and transportation

Before the automobile was invented and, in general, before motorization, the main means of transport was animal traction combined with the great invention of the wheel, in the form of carriages, wagons, carts, etc. From Antiquity to the end of the 19th Century, horses, donkeys, mules and other four-legged animals were used to carry people and goods.

A horse produces between 10 and 15 kilos of manure every day.

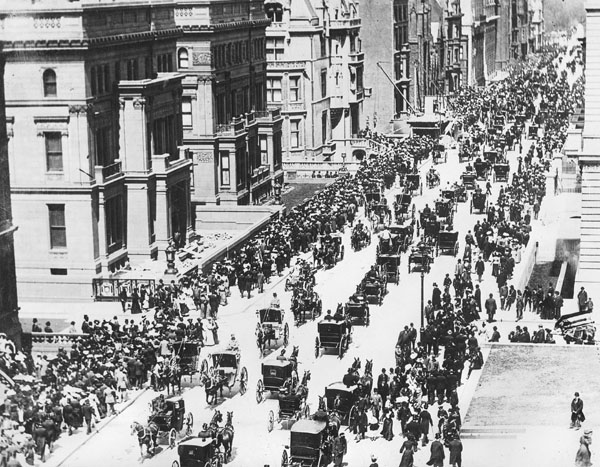

With the frenzied evolution of cities in parallel to the Industrial Revolution, came the increase of the population: London, Paris Rio de Janeiro, New York…millions of people migrated to the great metropolises in search of work and new wealth. With urbanization, came the urgent need for better transportation, since the distances in cities were becoming larger and larger.

The increase in population made these animals somewhat inconvenient: the horse-drawn carriages, in addition to noisy, hindered traffic in the streets, caused fatal accidents (in 1900, 200 New Yorkers were runover by these passenger vehicles) and, above all, were large producers of manure. The problem was that they were used for everything: rubbish was collected in carts, mail arrived on horseback, royalty greeted citizens from their wagons and funeral carriages were also horse drawn. And like any animal on earth, horses relieve themselves.

Fifth Avenue in 1900. Credit: Wikipedia

Bearing in mind that a horse produces between 10 and 15 kilograms of manure a day, it is devastating to imagine the accumulation of dung and the unsanitary situation that this caused. One of the most paradigmatic cases in this regard took place in New York.

New York, late nineteenth century

The U.S. city was a thriving urban centre by the end of the nineteenth century, with around 3.5 million inhabitants who, logically, needed to move around the town. At that time, there were about 170,000 horses also living in NYC (other sources put it at 200,000). By a quick calculation, we can estimate that each day in New York between one and two million kilos of equine excrement were "produced" every day, plus a litre of urine from each animal at least.

When the number of horses in the metropolitan was still manageable, there was a buoyant market for manure for agriculture purposes. Nevertheless, it was soon impossible to absorb the huge 'production' distributed around the city. There was so much of it that in some areas piles of up to 18 metres of droppings were accumulated, and farmers began to charge for taking the dung.

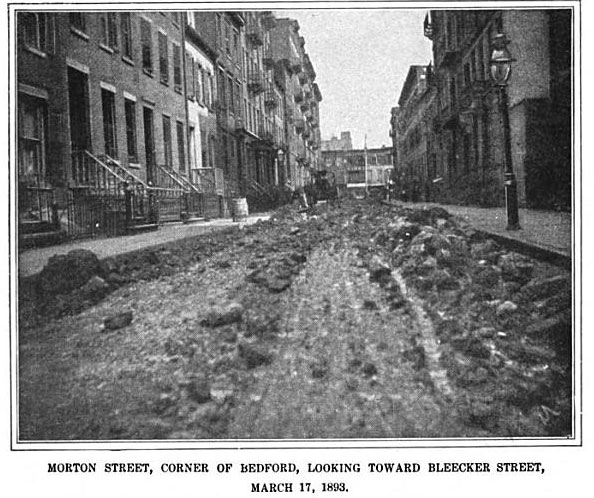

New York street during nineteenth century

On the other hand, since there was no specific area designated to leave the dung, the streets were constantly covered and made walking anywhere without getting dirty quite an odyssey. The rich could pay one of the many sweepers to clean their street, but most of the inhabitants had to manage as best they could.

Manhattan in 1903. Credit Wikipedia

New York authorities hired equipment to collect the manure at night, but the work was such that they could only clean the busiest avenues. The accumulation of faeces intensified with the rain, becoming a pestilent fluid that seeped into the basements, attracting all kinds of rats, flies and other disease-transmitting insects.

This largely determined one of the most distinctive features The Big Apple: the typical elevated staircases to the houses were born in order to avoid the "seas of manure".

Brooklyn. Credit Wikipedia

To make things worse, when these animals died, their carcasses were abandoned on the streets, creating an additional health issue.

In search of solutions

The situation was so dire that in 1898, New York Mayor George E. Waring Jr. organized the first international congress on urban planning, with manure as the "star" theme. This event, the first environmental summit in history, was attended by representatives from other cities to develop ideas on how to resolve the issue. Sadly, the lack of ideas to solve this ailment was such that, although a 10-day conference had been planned, by the third day, the conference had come to a close.

George E. Waring Jr. Credit: Wikipedia

Measures were put in place though: aside from staircases to access buildings, sewerage infrastructure was improved, and the first streetcar lines appeared (horse-drawn, but able to carry more passengers than a carriage); in addition, public transport was encouraged and street cleaning crews (known as White Wings because of their white uniforms) were established.

Street before and after street cleaning by George E. Waring Jr.

All of this contributed to stopping every citizen from using his or her own horse, and thus cleaning became manageable.

However, the real solution would arrive years later with the widespread use of cars. Years would go by before they became popular, and although nowadays it seems contradictory, two centuries ago, the automobile was a ‘green’ solution to the problem of horses and their manure.