We know young people are “angry, frustrated and scared” about climate change. And they want to do more to stop it.

However, the school system is not set up to help them address their concerns and learn the information they seek.

There are no explicit mentions of climate change in the Australian primary school curriculum and it is mainly taught through STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) subjects in high school.

More broadly, the main ways we talk about climate in the community and media are focused on science and economics. They tend to involve abstract ideas such as “the planet is warming” or “rainfall is more unpredictable”. While these are important components, they overlook the social, cultural and psychological ways people around the world are affected by climate change.

So, how can we better support schools and teachers to approach climate change in a way that will suit young people’s interests and concerns?

Our comic

We are geography and environment researchers who have written a comic that looks at how people around the world experience climate change. This is aimed at high school students, but will also appeal to university students and the broader public.

Called Everyday Stories of Climate Change, it looks at the ways low-income families have had to adapt to climate change in five countries across three continents.

It begins with a student, waking up in Australia and heading to school. Here the teacher notes that climate change is impacting people around the world, “today we are going to explore some of these places”.

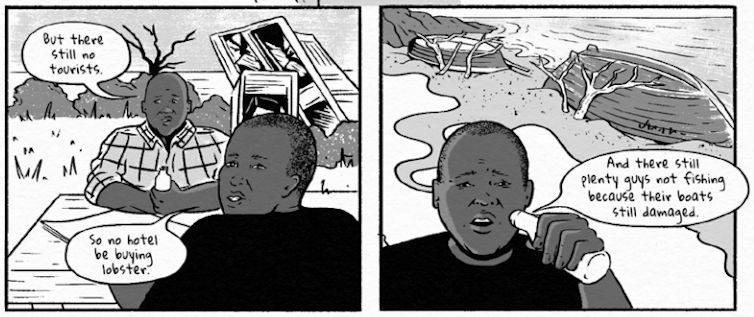

For example, in Bangladesh, sea-level rise has contributed to the salinity of the local river. So women must walk hours to get fresh water from another river. In Puerto Rico, after hurricane Maria, people struggle to get nutritious food and the streets are too dirty for the kids to play outside. In Barbuda, the government is trying to displace people from their lands, so that private businesses can build luxury hotels after hurricane Irma.

The characters in the comics are fictionalised but their stories are based on research – via interviews and surveys – the comic authors did about people’s experiences of climate change in Bolivia, Puerto Rico, Barbuda, South Africa and Bangladesh.

The importance of stories

Researchers have long argued we need to put a human face on climate change and communicate in ways that resonate with people. This means, we need to do more than present a graph or rattle off statistics.

Comics are an effective way to put a human face on issues because they allow us to show first-person narratives and experiences. This can create both understanding of the issues and evoke empathy in readers.

The comic is deliberately engaging and accessible. By showing real people going about their lives, it also challenges patronising ideas about people and places adversely impacted by climate change in the so-called “global south,” which often portrays them as “helpless” victims.

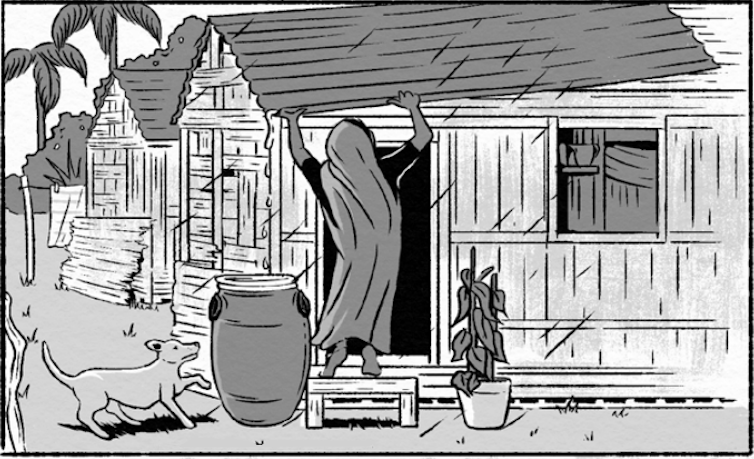

The comic also allows people to see the tangible, everyday ways people around the world live with, respond to and adapt to climate change.

For example, the family in Puerto Rico raise their own chickens and grow their own vegetables so they can eat the food they want during food shortages after hurricane Maria. In drought-stricken Cape Town, people save the bathwater for the garden and plant drought-tolerant aloes.

It is important to show these solutions as research suggests it gives people a sense of agency and hope they can adapt to climate change.

Parents, teachers and students can download the comic for free here and here.

Everyday Stories of Climate Change is a collaboration between Gemma Sou (RMIT University), Adeeba Nuraina Risha (BRAC University), Gina Ziervogel (University of Cape Town), illustrator Cat Sims and the Geography Teachers’ Association of Victoria.

![]()

Gemma Sou, Vice Chancellor's Research Fellow, RMIT University; Adeeba Nuraina Risha, Research associate, Brac University, and Gina Ziervogel, Associate Professor, Department of Environmental and Geographical Science and African Climate and Development Initiative Research Chair, University of Cape Town

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.