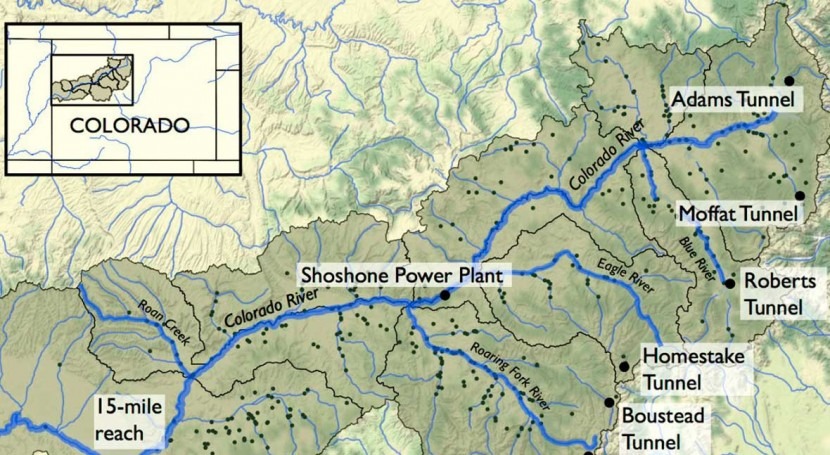

Within the Colorado River basin, management laws dictate how water is allocated to farms, businesses and homes. Those laws, along with changing climate patterns and demand for water, form a complex dynamic that has made it difficult to predict who will be hardest hit by drought.

Cornell engineers have used advanced modeling to simulate more than 1 million potential futures – a technique known as scenario discovery – to assess how stakeholders who rely on the Colorado River might be uniquely affected by changes in climate and demand as a result of management practices and other factors.

Their results are detailed in “Defining Robustness, Vulnerabilities, and Consequential Scenarios for Diverse Stakeholder Interests in Institutionally Complex River Basins,” published in the journal Earth’s Future. The report specifically examines a section of the Colorado River’s upper basin, where agricultural, municipal, recreational and industrial activities with rights to the water are worth an estimated $300 billion a year.

In Colorado, resource planning for the state’s major water basins is informed by a collection of databases, management tools and models developed by the Colorado Water Conservation Board and the Division of Water Resources. These tools have been used to conduct detailed studies of how specific water users may be impacted by climate change, but the studies considered only a few climate scenarios.

“Computing and other technical constraints limited their ability to explore combinations of human and climate pressures for the hundreds of stakeholders in the system,” said Antonia Hadjimichael, a postdoctoral researcher in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering and senior author of the paper. Patrick Reed, the Joseph C. Ford Professor of Engineering, is a co-author.

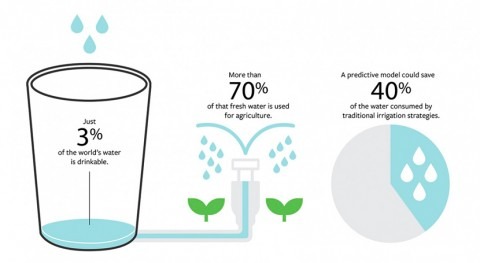

Public agencies want to know which potential changes cause individual water shortages so they can adapt their water management policies to address them. For instance, a boom in population suggests water conservation programs may be the best strategy, or limiting the growing season for a particular crop may offset water shortages due to irrigation.

“We were able to work together to consider a diverse set of potential futures in our exploratory modeling that helped us discover in finer-grained detail how individual water users’ vulnerabilities may differ substantially,” said Reed.

In order to account for the myriad laws, climate patterns and water demands, among other factors, Hadjimichael and co-authors used the Colorado Water Conservation Board’s model to simulate more than 1 million potential scenarios, depicting the Colorado River basin and its dependents in a collection of possible futures. The simulation offers a diverse view of each dependent’s vulnerability to a water shortage.

One key finding: Different local stakeholders experience the same drought in potentially very different ways, even when they are located near each other or possess similar rights to the water. This poses a challenge because studies that look at average vulnerabilities across groups – such as farmers, residents or businesses – or regions would miss critical details.

“For example, farmers located in the same county using water from the same river source might have very different water shortages during a drought,” Hadjimichael said, noting the model suggests historical data can’t always be relied upon to infer future impacts.

“These differences are due to complex relationships between their water rights, locations and the simulated future changes in climate and demands that we are still working to better understand,” Hadjimichael said.

Preparing for an uncertain future is especially important for the Colorado Water Conservation Board and other western U.S. policymakers as they continue to face unprecedented drought conditions. In the past two decades, the Colorado River basin has experienced its lowest period of inflow in more than 100 years of record keeping, and reservoir storage has declined from nearly full to about half of capacity, according to the U.S. Department of the Interior.

The paper’s authors suggest that the laws dictating rights to water resources are fundamental components shaping how stakeholders experience drought, and that predicting individual impacts requires models based on more than just simplified metrics and generic regional assessments.