As droughts become more frequent and intense, the fragmentation of water service in the U.S. among tens of thousands of community systems, most of which are small and rely on local funding, leaves many households vulnerable to water contamination or loss of service, a new Duke University analysis finds.

These vulnerabilities aren’t distributed equally, the study shows. Households in low-income or predominantly minority neighborhoods are likely to face the highest risks.

Resolving this disparity and making sure the taps in these homes don’t run dry will require a fundamental re-evaluation of how the nation’s patchwork of community water systems (CWSs) is managed and funded.

“Small water systems already are at a disadvantage when it comes to protecting water security during drought, because of the financial constraints they face,” said Megan Mullin, associate professor of environmental politics at Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment, who wrote the analysis. “Underlying patterns of segregation can amplify these weaknesses along economic and racial lines.”

Mullin published her peer-reviewed article April 17 in a special drought edition of Science.

Disparities in drinking water insecurity are rooted in segregation and the local political economy of public services, she explained. Because CWSs rely on user fees for their funding, they historically have extended service to neighborhoods or adjacent municipalities where residents are more able to pay. The result is that some communities get high-quality water service, while others – often rural communities or places where poverty is concentrated – get lower-quality service. Repairs or upgrades to pipes and other infrastructure are made less frequently, allowing leaks and increasing the potential risks of contamination. When drought arrives, these systems can’t cope.

Policymakers need to have a clearer understanding about the nature and extent of demographic disparities between water systems

“Drought aggravates vulnerabilities for small, under-resourced water systems. The user fee finance model then limits options for drought response, because policies that conserve dwindling water resources reduce revenue for water systems and make it harder for residents to pay their water bills,” Mullin said.

“Until now, people have tried to resolve these disparities through piecemeal approaches. We need to think more fundamentally about our reliance on user fees as a financial model for the delivery of such an essential service. States should consider equalizing resources across water systems to counter the legacy of racism and segregation, as we have done in public school funding,” she said.

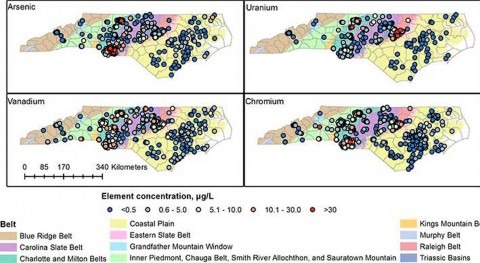

To do this, policymakers need to have a clearer understanding about the nature and extent of demographic disparities between water systems, she said. Recent efforts to develop maps of water system service areas in several states show promise, she said, and should be replicated nationwide and integrated with data on drinking water finance, infrastructure, and water supply and use. Over the last year, Mullin has been leading a team of Duke students to produce such a map of North Carolina water systems, through a partnership with the state’s Division of Water Resources.

“Of the 50,000+ community water systems delivering water year-round in the United States, more than 80% serve fewer than 3,300 people,” Mullin said. “Systems this small face tremendous challenges in delivering safe drinking water even under normal conditions, and as droughts become more frequent and intense, the challenges are going to mount.”

For these systems to become more resilient, they need to encourage and enforce water conservation. The strongest tools at their disposal for doing that are tiered pricing and mandatory use restrictions, but these reduce the water-use fees the systems depend on for funding and create an economic burden for low-income customers that could result in failure to pay and subsequent service shutoff.

Equalizing resources across water systems, as states already do for public schools, would circumvent many of these trade-offs and improve water security to millions of American homes.