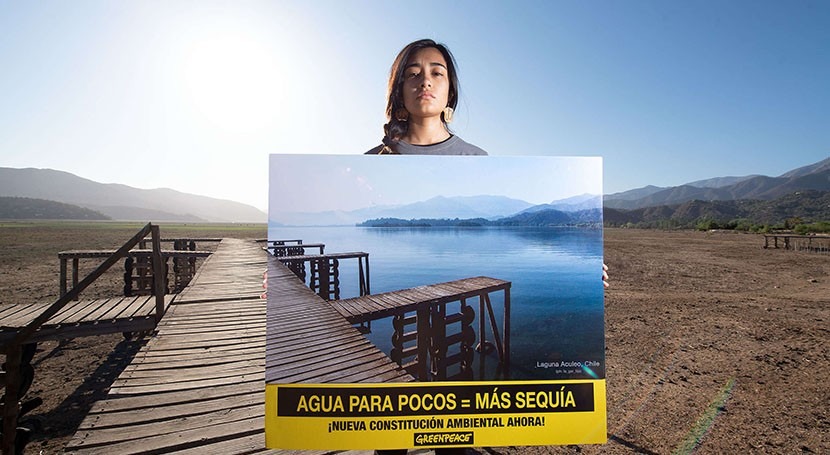

Chile’s Laguna de Aculeo dries up amid backdrop of water rights debate

Laguna de Aculeo, a lake in central Chile, has completely dried up. Although at first glance it seemed the result of the drought that has been affecting central Chile for the past decade, a recent analysis has revealed that the lake’s disappearance was due primarily to anthropogenic causes, mostly river deviations and aquifer pumping, reports Deutsche Welle.

Current dry conditions in central Chile are remarkable, even for a region with a semi-arid Mediterranean climate. But, according to the new study, although below-average rainfall over the past decade has had an impact, the lagoon had not dried out for thousands of years, whereas the “increase in legal water consumption in the watershed and its aquifer during the last decade or more has been outrageous”.

The most important change in land use in the area was the establishment of water-intensive fruit tree plantations starting around 2010. The aquifer’s main tributary, the Pintué River, was almost completely deviated, together with other important tributaries. The farms also withdraw water directly from the lagoon and through wells. As a result, "it didn't matter how much it rained anymore; for the first time, the lagoon was unable to support a drought”, said Pablo Garcia-Chevesich, a Chilean professor at the Colorado School of Mines and the University of Arizona and co-author of the study.

Garcia-Chevesich blames the loss of the lagoon on the “out-of-control assignment of water rights without any study or evaluation that includes climate change or social or ecological damage”.

Chile’s current constitution, dating from 1980, during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet, says water is a public good, but also states that allocations function as private property. Water rights can therefore be bought and sold. In addition, as per the 1981 Water Code, the authorities can grant those permanent and transferable water rights to private owners free of charge.

While the system helped Chile’s agricultural and mining companies thrive, after a decade-long drought and little oversight over the allocation of water rights, communities across the country are struggling for access to drinking water. The country is in the middle of redrafting its constitution with the help of 155 elected delegates from civil society. And one of the core issues is to change the legal nature of water, to ensure access to water for all. Water is part of a broader movement in the country to revamp an economic model that helped create a prosperous economy based on exploiting its natural resources, but has had high environmental costs and left many people behind; in fact, income inequality is higher in Chile than in most advanced economies, according to the OECD.

Progressive president Gabriel Boric, who has just taken office, has said he supports the constitutional change. He has named climatologist Maisa Rojas as environment minister, who plans to prioritise climate action. Climate change is expected to exacerbate the country’s water management challenges, and the decline in water reserves due to climate change was already a priority with the previous government. The issues at stake are complex, and the expectations are high from the new government.