The general long-term forecast for California as climate change intensifies: more frequent droughts, intermittently interrupted by years when big storms bring rain more quickly than the water infrastructure can handle.

This bipolar weather will have profound implications for the state’s $50 billion agriculture industry and the elaborate network of reservoirs, canals, and aqueducts that store and distribute water. A system built for irrigation and flood protection must adapt to accommodate more conservation. “The effects of climate change are necessitating wholesale changes in how water is managed in California,” the state Department of Water Resources wrote in a June, 2018 white paper.

During droughts, farmers and municipalities pumped groundwater to augment sparse surface supplies. After nearly a century of heavy use, many aquifers are badly depleted. And California’s five-year-old law regulating groundwater basins is nearing a moment of truth: in 2020, sustainability plans are due from agencies managing critically depleted aquifers. They must either find more water to support the aquifers or take cropland out of use. The law – the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, or SGMA – is beginning to bite. A 2019 study from the Public Policy Institute of California predicted that at least 500,000 acres of farmland will eventually be idled.

To ease the pain, engineers are looking to harness an unconventional and unwieldy source of water: the torrential storms that sometimes blast across the Pacific Ocean and soak California. “We need to capture the atmospheric rivers,” said Tim Quinn, the former director of the Association of California Water Agencies. But, he added, “We don’t have the right conveyance facilities. There’s not enough storage to capture the atmospheric rivers.” Quinn wants to capture stormwater and divert it to aquatic “parking lots,” as he calls them, where water can trickle back into depleted aquifers. This serves several ends: restoring a depleted natural resource, reducing land subsidence and providing for future water supply.

After passage of the law, groups including state and local water agencies, nonprofits, farmers, and agricultural groups like the Almond Board, are pushing to increase opportunities for recharge. “SGMA is a huge driver,” said Ashley Boren, executive director of Sustainable Conservation, a nonprofit working with farmers and local water agencies around the state. “There is a much greater interest in recharge than there was pre-SGMA.”

In the Tulare basin in the south, irrigation districts have long directed water onto special fields designed to allow it to percolate swiftly down and recharge aquifers. Now, “instead of sticking with the original recharge plans, we are aggressively recharging,” said Aaron Fukuda, general manager of the Tulare Irrigation District. “If someone can point to a hole one foot by one foot by one foot, I’ll go and put water in it.”

“Instead of sticking with the original recharge plans, we are aggressively recharging. If someone can point to a hole one foot by one foot by one foot, I’ll go and put water in it.”

Boren’s colleague at Sustainable Conservation, Daniel Mountjoy, said more than 120 million acre-feet of groundwater “has been pumped out of California aquifers” in the Central Valley in the last 70 or 80 years. He added, “I think of it as a giant underground reservoir that has already been built.” If you think about the cost of building one reservoir” — and the cost of environmental permitting – “why would we do that when we have access to 120 million acre-feet of capacity?”

Making the Central Valley Flood Again

How to tap into the atmospheric rivers? Ask Don Cameron, of Helm, who manages the Terranova Farm on the North Fork of the Kings River. He has flooded his vineyards since 2011. He has invested $14 million – $5 million from a DWR grant and another $9 million from Terranova – in diversion structures that will increase the amount he can recharge into the Kings aquifer’s sub-basin from 14 cubic feet per second to 500 cfs, or 1,000 acre-feet per day. (An acre-foot equals about 326,000 gallons; average California households use up to an acre-foot a year.)

For 38 years, Cameron has managed the farm, which grows 25 different crops, from tomatoes and garlic to wine grapes and, most recently, almond trees. “I noticed some time ago that the water table was declining two feet a year,” he said. “We realized we needed to do something.” His initial efforts to build recharge infrastructure – a pipe, a canal, and a spot designated for recharge – expanded nine years ago when he got a $75,000 grant from the federal Agriculture Department’s Natural Resources Conservation Service. This let him monitor “whether we could do groundwater recharge on working landscapes” – flooding his fields, both those fallowed and those where permanent crops, like grapevines, grew.

“We started flooding the wine grapes. We kept the water on from February to late June. The neighbors thought we were crazy, that we were ruining our grapes.” He wasn’t. Now he floods not only vineyards but nut trees. He works with DWR, promising to take excess water in flood years to prevent downstream flooding and has set aside 400 acres as a permanent recharge site and 1,200 acres more for seasonal recharge.

Flooded wine grapes at Don Cameron's farm on the north fork of the Kings River. (Photo credit: Terranova Farm)

His new system includes a large structure with gates that open to let water out of the north fork of the Kings River to a canal and the large pumping station to extract the surface water from the canal, plus a structure with gates that open to let water out of four new 72-inch pipes and into a canal, headed for recharge areas. He expects to be able to recharge at a rate of 500 cubic feet per second, which would equal 1,000 acre-feet a day, into the depleted aquifer. “The storage capacity beneath our feet is between 2 and 3 million acre-feet,” he said. “We have huge potential under our feet.”

He’s not alone. Anthea Hansen, general manager of the Del Puerto Water District, also wants to use flood irrigation to tap into atmospheric rivers; her district partners with another on a $2 million pilot project to recharge aquifers. Aaron Fukuda in Tulare helps operate a district using part of a $1.95 million federal grant to build a new recharge basin and study ways to expand existing recharge facilities. In the wet year of 2017, his district provided cheap water to farmers willing to put it back in the aquifer. But for an individual farmer, creating a recharge basin could be costly. Counting the price of land, engineering and excavation costs, a pipeline to move the water, and legal costs, a one-acre recharge project can cost $100,000, Fukuda estimates.

For agencies or individuals seeking to create new recharge basins, a new Stanford study offers a tool. The study, done by Rosemary Knight, an Earth Sciences professor, and a former Ph.D. student Ryan Smith — now an assistant professor at the Missouri University of Science and Technology — can help those building recharge ponds avoid the problems that plague the delivery system of the Friant-Kern Canal. Over-pumping made the land below it subside, torquing the structure and reducing its capacity. The study shows how a combination of satellite and aerial remote sensing, which map the underground sand and clay layers, can be used to predict how recharge can reduce subsidence. Combining the data sources allows creation of maps of the link between recharge — or continued groundwater pumping — and subsidence.

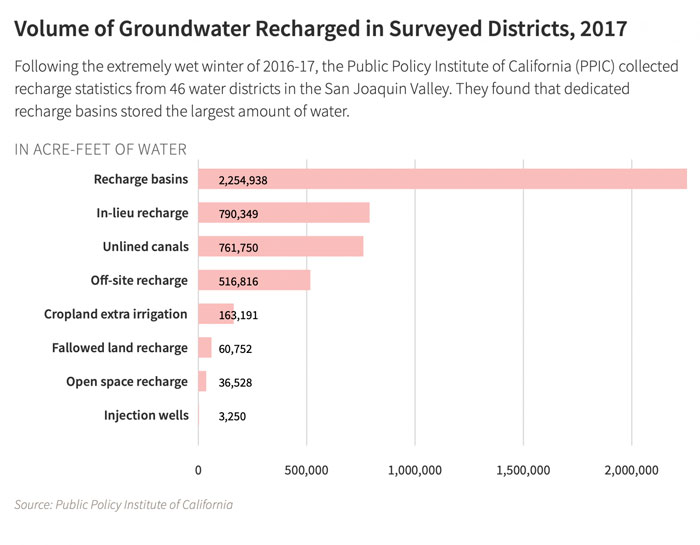

Recharge operations are nothing new; dedicated basins have dotted the San Joaquin Valley and the Sacramento Valley for years. Kern County’s Rosedale-Rio Bravo Water Storage District dates to 1959. Such operations helped raise the total of water recharged for the San Joaquin Valley to 6.5 million acre-feet in 2017 — a year, like the current one, soaked by atmospheric rivers. But the total amount of inflow to surface waters was closer to 30 million acre-feet, PPIC reported. While the volume of rain and the volume of recharge were exceptional, researchers say more recharge was possible. An annual average of about 500,000 acre-feet of recharge potential is available – about a quarter of the average annual groundwater deficit from over-pumping.

The state Department of Water Resources has a program devoted to improving on-farm recharge called Flood Managed Aquifer Recharge, or FloodMAR. Kamyar Guivetchi at DWR said they are working with the Merced Irrigation District to find out how much water could be recharged on farmlands in the Merced River watershed. Beyond that, he said, “We want to broaden the footprint” of new projects. The obstacles he sees goes beyond infrastructure. “It’s not about big infrastructure; it’s about big collaboration” among private, public and nonprofit interests.

Buzz Thompson, a Stanford law professor, focuses on the problem of moving the water. “The bottom line is that in the really wet years, we do not have the ability to store all the water that is available,” he said. Legal obstacles include the 120-year-old system of established individual rights to specific quantities of water. These must be met before the excess can be taken for recharge. So must requirements for environmental water deliveries ensuring fish get enough water. Most problematic: “Right now the greatest amount of surface water is available north of the Bay Delta and some of the best storage sites are south of the Delta,” he said. As long as the Delta is a transportation bottleneck, that limits the amount that can be stored.”

A Hitch: Who Owns the Recharged Water?

One incentive nudging farmers to do recharge is the knowledge that in dry years they will have access to the water they deposited in wet years. Irrigation districts and groundwater sustainability agencies don’t have a common approach to the question of credit. “With SGMA, each agency is going to establish its own rules,” said Mountjoy of Sustainable Conservation. “Does it belong to the farmer or the irrigation district that has a right to send it to the farmer?”

One school of thought favors collective ownership. “The water district has a right to take that water – it remains the irrigation district’s, for the benefit of all users,” Mountjoy said. A second option is “give the farmer the right to capture it and sell it. … They paid to put it in the ground. It’s now theirs. They could pump it out of the ground in a dry year or sell it to a neighbor. You basically create a water market.”

Kern County’s Semitropic Water Storage District practices a variant of this. “Our farmers can bank” recharged water “under the district’s established program. They have a bank account for their use,” said Jason Gianquinto, the district’s general manager. “We haven’t decided if they can do anything other than keep it for their own use. I can’t say you can move water outside our district to another area.”

Another Tactic: Releasing Water from Reservoirs When a Storm Nears

One way to capture more of the atmospheric rivers is allowing dams to release reservoir water in anticipation of a storm. The Army Corps of Engineers, which operates the reservoirs, has strict rules on how much water must be held and when it can be released. Now the Corps is working with tools developed by the Scripps Institute of Oceanography at the University of California at San Diego that facilitate what are called Forecast-Informed Reservoir Operations.

The Turlock Irrigation District uses the tools. “In 2017, when we had an excess amount of water, we were able to know what was coming. We could start making pre-flood releases,” said Josh Weimer, the district’s government affairs manager. The advance releases, some of which could be recharged, meant the 2017 flooding at its height was 25 percent of the flooding caused by similarly strong storms two decades earlier.

Across California’s farm country, the hard reality of a future without guaranteed access to groundwater is sinking in. Jerry Gragnani, a neighbor of Don Cameron’s who is 70 years old, recently sold 8,000 acres of his farm, keeping 3,000 acres for permanent crops like nut trees. “There’s no future without recharge,” he said. “I don’t think there’s a farmer around here that doesn’t realize that. We know if you don’t recharge the water, it’s going to run out. Once the aquifer is closed, it’s closed forever.” He added, “It’s a good time to get out.”

This article was originally published by The Bill Lane Center for the American West.