Wetlands, such as swamps and marshes, have some of the planet’s most valuable ecosystems. They act like sponges, preventing pollution from seeping into streams and other bodies of water, yet the depth of their federal protection is murky. In collaboration with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, a University of South Florida geologist has developed the first-ever classification system for wetland connectivity, helping improve water quality and management nationwide.

The new classification system, outlined in Nature Water, demonstrates the effects wetlands have on water quality at a continental scale – invaluable data that can be used to better define whether wetlands are federally regulated under the U.S. Clean Water Act.

“Since the Clean Water Act was established in 1972, we have continued to debate what constitutes our ‘nation’s waters,’ and wetlands continue to be lost due to draining and filling, despite their immense value in controlling the water quality in our major waterways,” said geology Professor Mark Rains, who was appointed by the state in 2021 to serve as Florida’s chief science officer. “However we define the ‘nation’s waters’ will have a huge influence on whether we continue to protect the remaining wetlands or if we will lose more.”

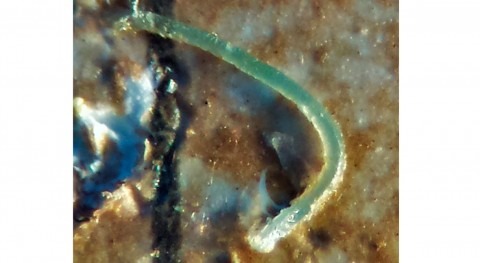

The team categorized freshwater wetlands into four classes based on their proximity to streams and whether water flows between them at or below the surface. They then used this classification system to show that wetlands play important roles in controlling a stream’s water quality.

In collaboration with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, a University of South Florida geologist has developed the first-ever classification system for wetland connectivity

The goal of this classification is to provide a better understanding of how wetlands contribute to the chemical, physical and biological integrity of downstream waters, especially nutrient runoff that can cause damaging algal blooms.

“It’s the disruption of these processes that has led to many of the water quality challenges we face today,” Rains said. “My hope is this will be the start of change for the way we think about wetlands, especially those not directly adjacent to streams. This was the most rewarding collaboration of my career – it was a great group of people who were really committed to doing science that serves the public.”

The EPA plans to make this classification system available for researchers to download and use. In addition to its impact on water quality, the system provides researchers and resource managers insight into improved methods for spatially targeting wetland restoration and protection.

“Until now, there hasn’t been a way to classify how wetlands connect to other waters at large scales,” said Scott Leibowitz, EPA research ecologist. “This has limited our ability to understand how wetland connectivity might contribute to water quality in watersheds.”

Rains says the research doesn’t stop here, as this classification system will likely lead to more projects in the near future. “We still have much to learn about how wetlands connect to downstream waters in different geographic regions,” Rains said. “This classification system gives us a place to start.”