Researchers at The University of Texas at Austin have created a balance sheet for water across the United States – tracking total water storage in 14 of the country’s major aquifers over 15 years.

The results were published in Environmental Research Letters on Aug. 17, 2021, with the research examining the interplay between irrigation habits and climate on water.

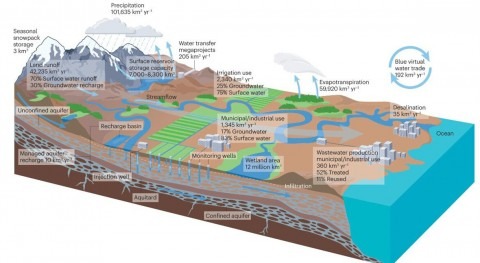

The study found that irrigation can be managed more effectively in humid regions of the eastern half of the United States where surface water is more readily available, a finding that could have implications for where the United States can grow food, according to the researchers. With longer-term droughts and intermittent intense flooding expected in the future, particularly in the arid western U.S., there is rising concern about overtaxing water resources in the region, especially for irrigated agriculture.

“It is important to understand the relationship between human water use and climate extremes to develop more sustainable water management practices in the future,” said the study’s lead author Bridget Scanlon, a senior research scientist at the UT Bureau of Economic Geology, a research unit of the Jackson School of Geosciences.

The study also highlights how surface water plays an important role in replenishing groundwater, with these water resources helping dampen the impacts of irrigation.

For instance, groundwater pumping for irrigation in the Mississippi Embayment Aquifer exceeded that of the California Central Valley, one of the most productive agricultural areas in the world. But satellite data showed that the Mississippi Embayment didn’t experience any long-term groundwater depletion despite the high levels of pumping. Researchers attributed this to groundwater pumping capturing water from the dense stream network in the humid Mississippi Embayment.

In contrast, in the semiarid western U.S. where droughts are much more prevalent, irrigation can amplify or dampen drought impacts depending on the source of irrigation water. For example, in the California Central Valley, irrigation switches from mostly surface water during wet periods to predominantly groundwater during droughts, amplifying the impacts of drought on groundwater depletion. This has led to groundwater depletion in the Central Valley totaling about 30 cubic kilometers, similar to the storage capacity of Lake Mead, the largest surface water reservoir in the U.S.

And in the northwest and northcentral U.S., widespread surface water irrigation likely helped total water storage in these aquifers remain stable or increase slightly, even though some areas faced similar drought conditions as the Central Valley.

A map showing total water storage change in cubic kilometers for 14 major aquifers over 15 years based on satellite data. A study led by The University of Texas at Austin used the data to examine how irrigation and climate influenced each aquifer’s water supply. Total water storage includes groundwater, soil water and surface water. Warm colors indicate aquifers that lost water. Cool colors are aquifers that gained water. Credit: Scanlon et al.

To understand how water changed over time, the researchers used measurements from NASA’s GRACE satellites taken from 2002-2017 to track the total amount of water stored in each aquifer area – including groundwater, soil moisture, surface water and snow.

The researchers also compiled climate data and irrigation records for each aquifer area and results from regional modeling by the U.S. Geological Survey. The climate data included information on precipitation and drought. The irrigation records included water volumes and whether the water came from surface water or aquifers.

By comparing the total water storage over time to climate and irrigation data, the researchers were able to describe how the water supply of each aquifer area was changing – and the role humans played in amplifying or dampening climate impacts on water storage.

Scott Tinker, the director of the Bureau of Economic Geology, said that the study’s insights on human influence offer critical information for managing water resources in the future.

“As we continue to study the impacts of climate extremes, it’s vital to also understand the impacts of human management practices on water and other natural resources,” he said. “This study makes significant progress towards that end.”

The study was funded by the U.S. Geological Survey Powell Center and the National Science Foundation.

The study was co-authored by Jackson School postdoctoral fellow Ashraf Rateb, bureau senior research scientist Alexander Sun, The U.S. Geological Survey’s Ward Sanford and Don Pool, The UT Center for Space Research’s Himanshu Save, Tsinghua University’s Di Long, and the National Drought Mitigation Center’s Brian Fuchs.