The deluge dumped on southeast Queensland and northern New South Wales this week has been catastrophic. Floodwaters peaked at around 14.4 metres high in Lismore – two metres higher than the city’s previous record.

So how does this compare to Australia’s previous floods, such as in 2011? And can we expect more frequent floods at this scale under climate change? The answers to questions like these aren’t straightforward.

Climate change doesn’t tell the whole story, as extreme rainfall can occur for a variety of reasons. What’s more, it’s too soon to officially state whether this event is directly linked to climate change, as this would require a formal event attribution study. This can take months or years to produce.

In any case, we do know extreme events like this will occur more frequently in a warmer world. And the rising death toll, ongoing evacuations and destroyed homes make this one of the most extreme natural disasters in colonial Australian history.

How this compares to floods in our past

The east coast is a common place for heavy rainfall and flooding. The Yugara and Yugarabul people have traditional stories about great floods in the Brisbane river region long before European colonisation, and sediments from floodplains indicate floods as severe as those in 2010–2011 have occurred at least seven times in the past 1,000 years.

Instrumental records and documentary accounts show severe floods have inundated southern Queensland’s cities and towns in the 1820s, early 1840s and 1890s, 1931, 1974 and, of course, in 2010–2011.

Each of these events have been devastating, and record-breaking, depending on which records you’re interested in.

The floods in 1841 and 1893 are considered highest in terms of water levels recorded in Brisbane city, reaching over 8m. Australia’s wettest day on record was also recorded in 1893, when Crohamhurst in the Glasshouse Mountains measured 907 millimetres in one day.

The 1974 event was associated with extreme rainfall totals in many coastal areas, including 314mm in one day in Brisbane, and more than a metre of rainfall was recorded over three days in places such as Mount Tamborine and the northwest of Surfers Paradise.

The 2010–11 flood, while not as severe in terms of extreme rainfall totals, was notable for its inland extent, and was the final act of Australia’s wettest July to December on record.

The current flood has peaked at 3.85m in Brisbane, below the 2010–2011 levels of 4.46m. But it’s breaking records in other areas such as Lismore in northern NSW. The rainfall statistics associated with this event are also nearing the highest on record for many places, possibly due to the slow-moving nature of the associated weather system.

Four of the top six highest rainfall totals in NSW were recorded on 28 February, and Brisbane has just experienced three days of over 200mm. These aren’t the highest daily totals ever recorded in the city, but the first time three days of such intense falls have been documented, in data that go back to 1841.

Disentangling the role of climate change

When it comes to understanding the role of human-induced climate change in extreme events, there is the temptation to ask the wrong question: “did climate change cause this event?”

Since any extreme event is always a manifestation of climate variability, large weather systems, local-scale weather and climate change, it’s impossible to categorically answer this question with a simple “yes” or “no”.

Instead, the question we should be asking is “did climate change contribute to this event?”

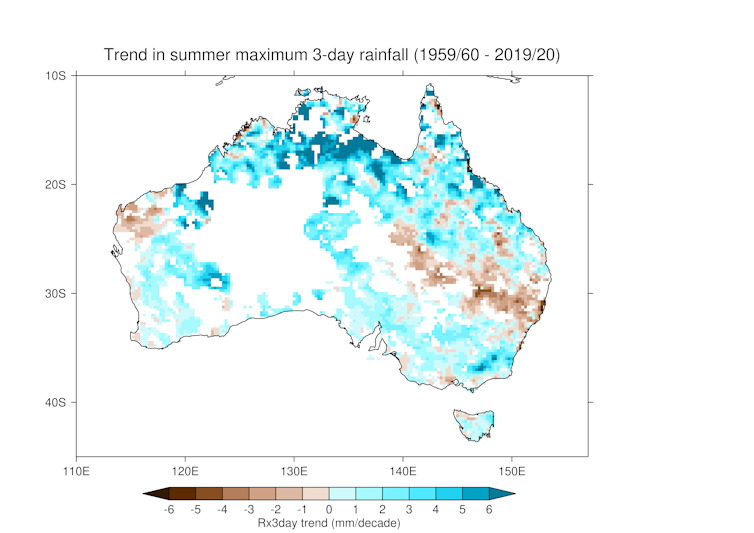

Well, firstly, there has actually been a slight decrease in summer rainfall in southeast Queensland and northeast NSW since the mid-20th century. But, there’s very high variability in rainfall for this region, and La Niña – a natural climate phenonenon associated with wetter weather – often brings flooding to this area, as we saw in 2010/2011 and in the 1970s.

Indeed, the effect of La Niña (and its counterpart El Niño, associated with drier weather) makes identifying a climate change-related trend more difficult. In other words, while a human-induced climate change signal may be present, the naturally high variability makes it hard to spot.

The atmosphere can hold approximately 7% more moisture for every degree Celsius of global warming. However, we also need the right weather systems in place to trigger the release of moisture from the air and cause extreme rainfall. The climate change effect on these systems is uncertain.

Climate change and weather systems

The severity of the flooding in southeast Queensland is partly due to a weather system called an “atmospheric river” sitting over the region for days. To make matters worse, the rain fell on an already sodden ground due to both the higher-than-average rainfall from the current La Niña, and the La Niña in the 2020-2021 summer. This made a huge difference to the scale of the floods.

We don’t fully understand how the persistence of these natural systems will change in future, but recent work shows climate change will cause long-lasting atmospheric rivers over Sydney to occur almost twice as often by the end of the 21st century. We don’t know yet if that’s also true further north of Sydney.

To complicate things further, there’s evidence to suggest climate change may be influencing the frequency, intensity and impacts of El Niño and La Niña events.

Climate change projections also suggest we may see small increases in the number of extreme one-day rainfall events which typically lead to flash flooding, in eastern Australia. But there’s a lot of uncertainty.

And worldwide, Monday’s report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projected that global warming of 2℃ this century will bring twice as much flood damage compared to 1.5℃ warming. This jumps to 3.9 times more flood damage at 3℃ warming.

While the role of climate change is hard to pin down in Australia’s biggest floods, we know flooding often strikes our east coast. Building greater resilience to severe flooding would help lessen their impact.

Taking steps like concentrating new housing and infrastructure projects in areas above flood plains would help make us less vulnerable to these events.

![]()

Andrew King, Senior Lecturer in Climate Science, The University of Melbourne; Linden Ashcroft, Lecturer in climate science and science communication, The University of Melbourne y Sarah Perkins-Kirkpatrick, Chief Investigator on the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes; ARC Future Fellow, UNSW Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.