Cornell geologists, examining the desolate Vavilov ice cap on the northern fringe of Siberia in the Arctic Circle, have for the first time observed the rapid ice loss from an improbable new river of ice, according to new work in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Observing the ice cap over a period of years, the researchers thought they were seeing a glacial surge, a temporary condition in which snow buildup ebbs and flows over long time scales.

But in this area of the world that is frozen for most of the year, that glacial surge grew faster, wider and fanned out. Having shed nearly 11% of its mass – or 9.5 billion tons of ice since 2013, it may become a more-permanent, impactful ice stream, researchers say.

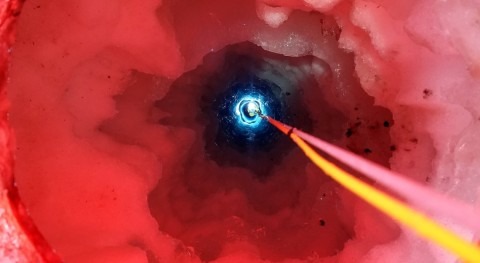

“This is the first documented case of an ice stream being formed. We really didn’t expect to see this,” said lead author Whyjay Zheng, Cornell doctoral student. Now, after about six years of study, the stream resembles a triangular-shaped fan, bordered by dark-shaded crevasses. At the wide center channel, the stream ice flows at a relatively high speed – around 3 miles per year.

The Vavilov ice cap in the Arctic Circle is now experiencing rapid ice loss by way of an ice stream, shown here. It has shed 9.5 billion tons of ice since 2013.

“In the satellite images, it seems like the entire west wing of the ice cap is just dumping into the sea,” Zheng said. “No one has ever seen this before.”

Until this ice stream discovery, the only other places where geologists had seen ice streams were Antarctica and Greenland.

“This glacier went from doing basically nothing to doing something very unusual – evolving into an ice stream,” said Matthew Pritchard, professor of earth and atmospheric sciences and a fellow at the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability.

Could the stream be a result of climate change? Yes, Pritchard said, as a portion of the surface of the Vavilov ice cap melts each summer. The ice cap can be compared to much larger marine ice sheets that reach the ocean, which can be eroded by warm water and become unstable when supporting ice shelves are lost.

Once the frozen support collapses, the researchers said, ice streams may form, which allows the ice to flow into the ocean in a surprisingly short time.

Pritchard said this ice stream’s relationship to global warming is “hard to ignore,” although researchers are still puzzled by its existence. “The Vavilov ice cap is not a place where warming has hit very hard,” he said. “Yet we’re still seeing this change. It’s a new river of ice we’re trying to understand.”

Zheng points out that mass lost at the Vavilov ice cap is no longer recoverable.

“This is offering scientists another clue as to what happens during global warming. Now once the ice is lost, it is lost,” he said. “Suddenly, we have more water in the oceans.”