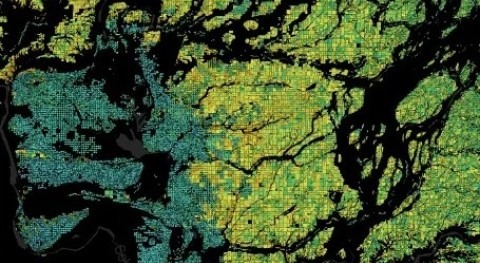

Climate change is here, and scientists continue to discover new ways that the world around us is changing. In a new study published in the May issue of the Journal of Hydrology, DRI researchers show that altered weather patterns are impacting stream flows across the country, with implications for flooding, drought, and ecosystems.

Led by Abhinav Gupta, Ph.D., a Maki postdoctoral fellow at DRI, the research examined how day-to-day variations in streamflow changed in more than 500 watersheds in the U.S. between 1980 and 2013. They found that increased winter temperatures have driven the changes, with impacts varying due to local climate and amongst snow and rain-dominated watersheds. This information is important, the researchers say, for helping water managers adapt to climate change’s impacts.

“We wanted to understand how climate change has impacted the hydrological balance across the U.S. based on the observed data,” Gupta says. “Once we understand how climate change has impacted stream flows in the recent past, we can figure out what kind of changes we might see in the future.”

Streams receive water from a variety of sources, including fast, direct input from rainfall, and groundwater that gradually seeps through springs and soil. To understand how climate change is altering stream flows over time, the authors needed to differentiate between normal variability, like seasonal changes, and longer-term trends. To do this, they broke down stream inputs into events that occur at different timescales, like hourly and daily (rainfall), vs monthly and annual (groundwater). Then, they looked at trends for each timescale to see how they changed over time.

Altered weather patterns are impacting stream flows across the country, with implications for flooding, drought, and ecosystems

“Once we understand how these trends are evolving, we can make educated guesses about what exactly is changing in the watershed – whether it is snowmelt, surface runoff, base flow, or one of many other factors,” says Gupta. “Without studying streamflow in this way (what is called streamflow statistical structure) it’s not possible to study all of these components together, at once.”

Their results show that snow-dominated watersheds across the country are receiving more precipitation as rain than historically. This means that streams now have more water coming in short bursts from rainstorms, rather than the slow trickle of melting snow. The shift to short-term stream inputs could also be attributed to faster snowmelt rates due to higher temperatures, the authors say.

“In the past, streamflow changed very slowly over time,” Gupta says. “But now, because of climate change, we have faster fluctuations in streamflow, which means that we can have a lot of water in a very small amount of time and then we can have no water for a long period of time. These extreme swings are occurring more and more.”

Although the researchers found increased temperatures and changes in rainfall in all watersheds, differences in local climate dictate how this influences streamflow. In humid locales like Florida and the Pacific Northwest, storm inputs decreased, as higher temperatures caused more evaporation, leading the soil to absorb more rainwater. In the Great Plains and Mississippi Valley, contributions to streams from slow, long-term inputs like groundwater are very low, likely also due to high evaporation rates. Arid watersheds saw an increase in the number of days each year without rainfall over the study period, as well as a significant increase in winter temperatures, making streamflow more sporadic.

The study didn’t examine other variables that could impact how water moves through watersheds, like changes in forest cover that impact the amount of water used by plants, or soil type, which affects how quickly rainfall permeates into groundwater. Because each watershed is unique, with its own recipe of soil type, climate, and forest cover, “we cannot paint everything with the same brush,” Gupta says. “We need different strategies for different watersheds to adapt to changes in climate. Even within the same region, watershed impacts can vary.”

More research is needed, the study authors say, to understand what is driving changes in streamflow. If streams are increasingly dependent on groundwater, this could impact how water managers regulate groundwater pumping for human use. “That’s the kind of thing we need to know moving forward, in terms of how we manage our water resources,” says Sean McKenna, Ph.D., study co-author, and Clark J. Guild, Jr. Endowed Chair and Director of hydrologic sciences at DRI. “Can we pump more groundwater, or do we need to be more careful because if we do, we could lose streamflow?”

Gupta says that he plans to build on this research. “Based on this study, we have been able to identify watersheds across the U.S. that have changed. Now that we know which watersheds in our dataset have been affected by climate change, we can look at the future changes in those watersheds.”