The geology along Ecuador's Coca River is moving in fast-forward. In a scientific field where natural wonders form over millennia, but natural disasters occur in minutes, speed is less than desirable.

Over the last four years, the river and its surrounding area within the Amazon basin have experienced a lava dam collapse, 500 million tons of sediment displaced down the river, landslides and the formation of what some have dubbed the "Ecuadorian Grand Canyon."

In the wake of these events, bridges and pipelines have collapsed, collapsing riverbanks have threatened homes and businesses, and Ecuadorian engineers feared the rapidly dropping headwaters of the river could take out a hydropower plant that provides electricity to one-third of the country.

These impacts and threats brought together an international group of experts, including Matt Larson and Brandon Stockwell from the Autonomous Systems group at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Larson and Stockwell used drones to map a previously unstudied section of the Coca River.

The team's high-resolution visual, thermal and multispectral imagery will be used to update Ecuador's national maps and create better engineering models to mitigate the erosion.

To better understand the gravity of their mission, let's rewind. On Feb. 2, 2020, the San Rafael waterfall disappeared. Journalists and geologists have used various words to describe what happened to Ecuador's largest waterfall four years ago. Whether the natural wonder "failed," "collapsed" or was "abandoned," the singular phenomenon on the Coca River that day began a cascade of geographic events that continue to impact the country's landscape, infrastructure and security.

Pedro Barrera Crespo, a hydraulic engineer and consultant for the Corporación Eléctrica del Ecuador, or CELEC, the country's major electric utility, had no problem landing on a word for it—"alarming."

What actually happened? The San Rafael Waterfall was formed thousands of years ago when volcaniclastic debris from the nearby Reventador Volcano formed a natural lava dam in the Coca River. It was once the tallest waterfall in Ecuador, plummeting from a height of approximately 150 meters, or 490 feet, amidst dense tropical rainforest. The river flowed over the lava dam, though the waterfall into a basin from where it continued another 400 miles before meeting with the Amazon River.

Just upstream of the lava dam, a sinkhole formed in the riverbed. On Feb. 2, 2020, the sinkhole roof collapsed, dropping the river flow below the lava dam rather than over it. The river continued to flow, but one of Ecuador's greatest tourist attractions was lost forever.

The losses would continue to compound in the following months as the eaects of this unique event unfolded. It's easiest to explore the waterfall collapse fallout in two sections—upstream and downstream—of the lava dam.

Upstream: Erosion, headcut and a hydropower threat

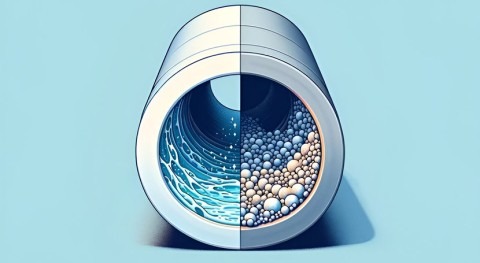

The sinkhole collapse left behind a sharp change in the riverbed slope, known as a headcut, just upstream of the lava dam. Freshly exposed riverbed material at a headcut is unstable, causing rock and soil to erode in the opposite direction of water flow. In the first 18 months following the waterfall event, the Coca River's headcut regressed 12 kilometers, just over 7.4 miles, upstream as the water washed away the earth beneath it.

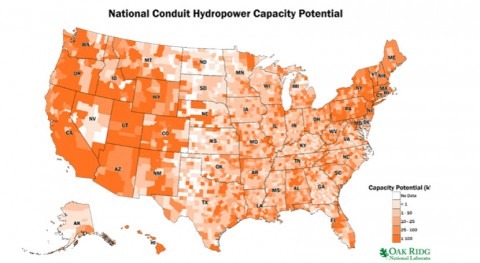

If the erosion had continued at this rate, Ecuador's largest hydropower plant, located just 19 kilometers, or 11.8 miles, upstream of the waterfall, would likely have lost operation.

The Coca Codo Sinclair Hydropower Facility supplies 26% of the country's electricity.

Pablo Espinoza Girón, who leads the CELEC subcommission on the Coca River, said CELEC initially launched a study after the sinkhole collapse to understand the near-future implications for the hydropower plant.

"It was really a big warning for CELEC after that study because the results were alarming," Girón said. "The potential implications were really dire for the plant."

The implications being: If the river headcut were to erode its way upstream to the hydropower plant, the river would undermine the plant's water intake. Without water, the plant can't generate electricity, resulting in massive consequences for Ecuador's people and commerce.

"It would be the U.S. equivalent of a power failure encompassing all the East Coast and some adjacent states," ORNL's Larson said.

Luckily, the head cut erosion slowed because of a combination of more stable riverbed materials closer to the hydropower plant and unusually dry river basin conditions since 2022. Still, erosion is worrisome for the country's power supply as well as the surrounding landscape and infrastructure. The threat of collapse remains ever-present as the river continues to flow.

Downstream: Sediment deposition

As upstream erosion and landslides continue, the rocks, sand, soil and other natural riverbed debris flow downstream. In total, there are 500 million tons of sediment moving down the Coca River. This heavy, moving sediment is a force, as it carves out land among the river, causing oil pipelines, bridges and parts of a major roadway to collapse.

Adriel McConnell of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, or USACE, attempted to put the Coca River sediment load since the 2020 waterfall collapse into perspective.

"The sediment we're talking about that has moved in this now-12-kilometer, or approximately 7.5 miles, stretch of the Rio Coca is 1.25 times more sediment than moves through the mouth of the Mississippi River on a yearly basis," McConnell said.

For additional insight, the Mississippi River is over 300 times the length of the Coca River segment the sediment wave has passed through.

Similar to upstream quandaries, the greatest potential impact downstream of the waterfall collapse involves the Coca Coda Hydropower Plant. During normal operation, the plant channels water from the upstream intake to the hydropower plant, 65 kilometers, or about 40 miles, downstream. It then discharges the used water back into the river.

As the used water sludges its way downstream, the 500-million-ton sediment wave could eventually block the power plant outlet structure, leading to electricity generation shutdown. This shutdown would impact the equivalent of the entire US eastern seaboard losing electricity.

Matt Larson and Brandon Stockwell, part of ORNL's Autonomous Systems Group, stand with a drone above the Coca River where they mapped 102 kilometers of the previously unmapped area. Credit: Matt Larson, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, US Department of Energy

Calling in reinforcements

With a two-pronged predicament threatening a major utility source, in addition to infrastructure and natural resources, the Ecuadorian government and the U.S. Ambassador to Ecuador called for help. Reinforcements included McConnell's USACE team as well as experts from other national organizations such as the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, or NGA, to help mitigate the eaects of this unique phenomenon. Additionally, the U.S. Geological Survey started helping develop a sediment monitoring plan to better characterize the soils in the area, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture conducted soil jet testing to determine soil erodibility.

"Our mission is focused on projects to control this erosion profile and stabilize it before it reaches the intake. We're helping Ecuador monitor the downstream sediment as it progresses to determine, not so much if, but when they need to do a massive project to relocate the outlet structure further downstream," McConnell said.

The Ambassador also made a special request for ORNL's Larson and Stockwell to join the effort. Together, they brought to the mission previous experience, advanced skills and expertise in conducting remote operations. And the drones.

"It's over 1000-foot clia down to the river in some areas," Larson said. "You just can't go and see what's happening. The only way to really do this is by drones."

ORNL's specialized skills

Larson is a research scientist in ORNL's Autonomous Systems group with a background in geology and geospatial technology. In fact, Larson said while in graduate school he used the same drone model they took down to Ecuador to map river sediment. In other words, he was well suited for the job.

"This was right up my alley," Larson said. "I never thought I would map sediment again in my research career, but here it is."

The mapping is only one part of the job—Larson also helped process all the data the drones collected using ORNL's high-performance computing resources. Translated and compiled, these data were used by CELEC to create models for mitigating the effects of the natural disaster on the Coca River and Ecuador's infrastructure.

The Ecuadorian government, USACE and NGA had done some initial surveying after the San Rafael waterfall collapse, but ORNL's capabilities in the field and in the lab brought unmatched capabilities to catch up with Mother Nature.

"Data is king," USACE's McConnell said. "The numerical modeling and computer modeling to predict these erosion and sediment timelines is where Oak Ridge has become a very key player for us."

While Larson brought the science and data processing background to the mission, he wasn't used to operating in remote environments. Enter Stockwell, an autonomous systems specialist at ORNL and US Marine Corps pilot. A complement to Larson, he's well versed in operating drones and brought his own set of skills to the Coca River team in November 2023.

"As far as deployments and austere environments, that's nothing new for me," Stockwell said. "I've done a lot of deployments so it's almost second nature to go out on expeditionary operations."

An under (cloud) cover mission

Larson, Stockwell and their team planned to map the previously unmapped stretch of the Coca River, spanning 100 kilometers, or 62 miles. They had support from the USACE, including McConnell; Mike Shellenberger and Shawn Smith from NGA; and from CELEC who bridged language barriers and provided regional and historical knowledge. With the team's veteran experience spanning the Marine Corps, Army and Air Force, their planning naturally mirrored military mission operations.

The team met to take stock and coordinate their assets "and say, 'Can we accomplish this with the assets we have on hand?'" said Shellenberger, NGA Warfighter Support Office contractor and former Army Special Forces soldier who was part of the project. "That's all part of planning a military operation, essentially."

Though the team had the right people in place, their work was cut out for them: Mapping 100 kilometers of a river in 15 days with two drones and zero existing maps was no small feat. The constant cloud cover over the Coca River is so thick, no helpful satellite imagery existed. The unyielding vegetation in the Amazon basin also made map-making seemingly impossible.

"It was a big mission set that Matt agreed to as far as the amount of mapping we were going to do with drones ... in two weeks," Stockwell said. "The maps we were using to plan out missions were just clouds, or it was such old imagery it was like guesstimating where it was safe to fly."

These conditions made drones mission-critical: They could fly under the clouds and launch vertically, giving the team flexibility amid the rough landscape. With a time-limited schedule, the team plotted out the kilometers they aimed to map each day, with some flexibility for the conditions.

"It's always cloudy. It's always raining. Satellite imagery isn't good," Larson said. "Drones are the only way to map this area."

Shellenberger acknowledged this as well, noting that although they had the right equipment, Mother Nature brings her own agenda.

"It's one of the most terrain- and weather-restricted environments I've ever been in," Shellenberger said. "We had to build that into our timeline." Shellenberger added, the team also had to consider "Murphy" in their planning—a military term that harkens back to Murphy's Law, which states anything that could go wrong will go wrong. And the team certainly encountered Murphy during the mission.

While the unpredictable weather was a known variable, factors such as magnetic rocks presented unexpected challenges. "You have to give Murphy his due," Shellenberger said. "You can plan out and think of everything that could go wrong and have all these contingencies built into your plan, but there's this one thing that you had no control over and that can throw a kink in what you're trying to accomplish."

Iron-rich rocks and sediment from volcanoes in the area littered the ground where the team needed to launch their drones. In addition, the magnetic quality interfered with the compasses on the drones, making launches a challenge.

"We'd set it on the ground and get an error," Larson said. "We had to get creative on how to launch the drones."

Larson and Stockwell described launching drones oa stacked equipment cases and even their own hands. Murphy also surfaced in the form of unexpected flight conditions. Stockwell said the combination of valley, water and mountains surrounding them created variable wind speeds and directions. The team also, at times, needed to fly the drones from a different perspective than usual: Typically, drone pilots are looking up at the device they're controlling. The team did this when down in the Coca River riverbed.

However, the team also piloted the drone from above, while standing on the clias, 1,000 feet over the river. This angle could affect both navigation and communication connections.

Larson said the Ecuadorian military granted them authorization to thwart certain drone flight regulations to complete the mission, such as flying below 400 feet and keeping the drone within direct visibility.

"We were able to really push the limits of drone operations down there," Larson said. "That gave us the ability to fly at whatever altitude we wanted as well as beyond visual line of sight."

"If it weren't for [the Ecuadorian military], I don't think we would have actually mapped the 100 kilometers."

Depending on the kindness of strangers

The team relied on help from Ecuador's civilians as well. At times, the only places to launch were in privately owned fields or backyards. In these cases, CELEC representatives assisted by knocking on doors and speaking with people about the mission. Most of the community had no problem letting the team launch drones on their property.

Larson said people were not only understanding but welcoming. He grinned as he retold a particular story that highlighted this hospitality. One day they found the perfect launch location at a school soccer field that overlooked 10- 15 kilometers of the river they needed to map. After speaking with several townspeople, Larson said the team found the school principal's house. They knocked on the door and asked permission to access the school grounds for launching drones.

The principal obliged. She sent her elementary-aged son to unlock the school gate. He hopped on his scooter and led the team's truck to the school a few hundred meters away.

"That was a big, critical moment for us because if we didn't have access to that school, we would have struggled to find a good spot to launch," Larson said. "The Ecuadorian people are so nice, and they understand what's happening down there."

Landslides caused by river erosion and sedimentation were taking out the village's roads along the river. Many used public transportation to commute to Quito, the country's capital, for work. Others relied on the main road for transporting goods in and out of the village. Larson said if a particular bridge along the main road were to be undercut by the landslides, it would take an additional 10 hours to drive from the village to the capital.

A mountain of data, a river of results

The team completed the mission of mapping over 100 kilometers, around 62 miles, of the Coca River in under 15 days. Larson returned to the U.S. and began processing the two terabytes of data the drones gathered. The high-performance computing capabilities at ORNL were crucial to this part of the mission.

"You don't want to take a laptop and try processing 52 flights. That takes forever," Larson said. "Using our computing resources at the lab has been really beneficial."

Before Larson and Stockwell visited Ecuador, CELEC teams collected 10 to 20 kilometers of topographic information about every two months using basic drones and technology.

ORNL's team was able to accomplish in two weeks what previously may have taken eight months or longer. Larson helped transform the drone maps into centimeter-resolution 2D and 3D models which are now being used to update the national maps of Ecuador, and to make better engineering models for the CELEC and the Army Corps of Engineers.

These models will help CELEC and their partners to outpace the erosion and sedimentation rates. "It will really help them understand spots with a high potential for a landslide," Larson said.

"But also, they can look at, 'okay if we do need to rebuild a bridge, where can we rebuild it?' When we say, 'kilometer 60,' we know exactly where that is."

McConnell said the team will first stabilize the erosion zone upstream of the former waterfall location in Spring of 2024. Then, he said, attention will turn to curbing the eaects of the sediment load moving downstream.

"It's professionally exhilarating to work together to find a solution," McConnell said. "You know you're charging into the great unknown—there's no road map for this." Espinoza Girón said, after looking at the models, the group is considering several options for sedimentation mitigation, including a diversion tunnel that would bring the hydropower plant outlet structure further downstream to avoid being buried in sediment.

Another option he mentioned was creating artificial knickpoints, or sharp drops, in the riverbed, which would recreate how a river might form naturally and slow the erosion from the flowing sediment.

The chosen path could be a bellwether for future geology events of this sort. Barrera Crespo added that the speed at which the Coca River erosion and sedimentation progressed created a unique case study for the hydrogeology field. He hopes it will highlight the need for proper sediment management as new dams are built, now that the effects can be seen over months instead of the normal decades it takes for a riverbed to settle and erode.

"Sediment transport-related problems in rivers are not so easy to see in normal timescales," Barrera Crespo said. "This is basically a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity we have to tackle this problem. With the help of world-renowned expertise, this has been a valuable opportunity for everyone."

For Larson, the most important part of the mission is the ability to help Ecuador's people and their land. But it's also a watershed moment for his career.

"Meeting all the people down there and seeing the impact that we could provide are definitely going to be among the highlights of my career," Larson said. "I'll remember this for the rest of my life."

UT-Battelle manages ORNL for the Department of Energy's Oaice of Science, the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States. The Office of Science is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.