The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) has officially confirmed that 2023 is the warmest year on record, by a huge margin.

The annual average global temperature approached 1.5° Celsius above pre-industrial levels – symbolic because the Paris Agreement on climate change aims to limit the long-term temperature increase (averaged over decades rather than an individual year like 2023) to no more than 1.5° Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

Six leading international datasets used for monitoring global temperatures and consolidated by WMO show that the annual average global temperature was 1.45 ± 0.12 °C above pre-industrial levels (1850-1900) in 2023. Global temperatures in every month between June and December set new monthly records. July and August were the two hottest months on record.

“Climate change is the biggest challenge that humanity faces. It is affecting all of us, especially the most vulnerable,” said WMO Secretary-General Prof. Celeste Saulo. “We cannot afford to wait any longer. We are already taking action but we have to do more and we have to do it quickly. We have to make drastic reductions in greenhouse gas emissions and accelerate the transition to renewable energy sources,” she said.

“The shift from cooling La Niña to warming El Niño by the middle of 2023 is clearly reflected in the rise in temperature from last year. Given that El Niño usually has the biggest impact on global temperatures after it peaks, 2024 could be even hotter,” she said.

“While El Niño events are naturally occurring and come and go from one year to the next, longer-term climate change is escalating, and this is unequivocal because of human activities. The climate crisis is worsening the inequality crisis. It affects all aspects of sustainable development and undermines efforts to tackle poverty, hunger, ill-health, displacement, and environmental degradation,” said Prof. Saulo (Argentina), who became WMO Secretary-General on 1 January 2024.

Since the 1980s, each decade has been warmer than the previous one. The past nine years have been the warmest on record. The years 2016 (strong El Niño) and 2020 were previously classed as the warmest on record, at 1.29 ±0.12°C and 1.27 ±0.12°C above the pre-industrial era.

Based on the six datasets, the ten-year average 2014-2023 was 1.20 ±0.12°C above the 1850-1900 average, factoring in a margin of uncertainty.

Consolidated global temperature datasets for 2023. Credit: WMO

“Humanity’s actions are scorching the earth. 2023 was a mere preview of the catastrophic future that awaits if we don’t act now. We must respond to record-breaking temperature rises with path-breaking action,” said UN Secretary-General António Guterres.

“We can still avoid the worst of climate catastrophe. But only if we act now with the ambition required to limit the rise in global temperature to 1.5 degrees Celsius and deliver climate justice,” he said in a statement.

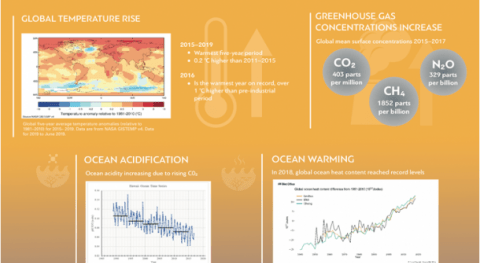

Long-term monitoring of global temperatures is just one indicator of climate and how it is changing. Other key indicators include atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations, ocean heat and acidification, sea level, sea ice extent and glacier mass balance.

WMO’s provisional State of the Global Climate in 2023 report, published on 30 November, showed that records were broken across the board.

Sea surface temperatures were exceptionally high for much of the year, accompanied by severe and damaging marine heatwaves. Antarctic sea ice extent was the lowest on record, both for the end-of-summer minimum in February and end-of-winter maximum in September .

These long-term changes in our climate play out through our weather on a day-to-day basis. In 2023, extreme heat impacted health and helped fuel devastating wildfires. Intense rainfall, floods, rapidly intensifying tropical cyclones left a trail of destruction, death and huge economic losses.

WMO will issue its final State of the Global Climate 2023 report in March 2024. This will include details on socioeconomic impacts on food security, displacement, and health.

Official datasets

The WMO consolidated figures are based on six international datasets to provide an authoritative temperature assessment.

WMO uses datasets based on climatological data from observing sites and ships and buoys in global marine networks, developed and maintained by the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (NASA GISS), the United Kingdom’s Met Office Hadley Centre and the University of East Anglia’s Climatic Research Unit (HadCRUT), and the Berkeley Earth group.

WMO also uses reanalysis datasets from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts and its Copernicus Climate Change Service, and the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA). Reanalysis combines millions of meteorological and marine observations, including from satellites, using a weather model to produce a complete reanalysis of the atmosphere. The combination of observations with modelled values makes it possible to estimate temperatures at any time and in any place across the globe, even in data-sparse areas such as the polar regions.

2023 was ranked as the warmest year in all six datasets.

Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement seeks to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels while pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says that climate-related risks for natural and human systems are higher for global warming of 1.5 °C than at present, but lower than at 2 °C.

A study by WMO and the UK’s Met Office last year predicted that there is a 66% likelihood that the annual average near-surface global temperature between 2023 and 2027 will be more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels for at least one year.

This does not mean that we will permanently exceed the 1.5°C level specified in the Paris Agreement, which refers to long-term warming over many years.

The chance of temporarily exceeding 1.5°C has risen steadily since 2015, when it was close to zero. For the years between 2017 and 2021, there was a 10% chance of exceedance.