Mounting public concerns and new state regulations in the U.S. are compelling water & wastewater utilities to address health risks associated with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) – a class of pervasive chemicals found in drinking water and wastewater biproducts.

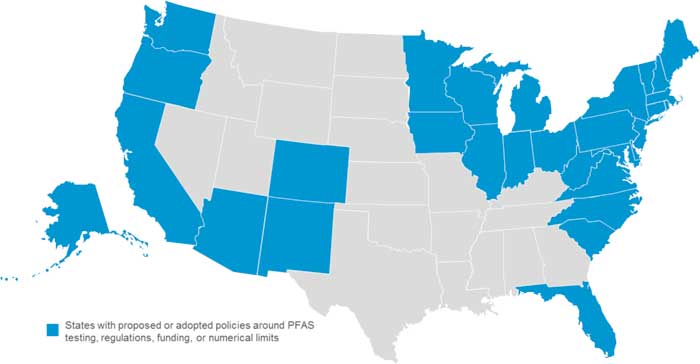

According to a new report from Bluefield Research, PFAS: The Next Challenge for Water Utilities, more than US$3 billion is forecasted to be spent annually on drinking water remediation technologies by 2030. While any significant increase in water treatment solutions hinges on federal policies, 29 states have already implemented a mix of policy directives, including testing requirements, prohibitions on product applications (e.g., food packaging), firefighting foam constituents, and uses for manufacturing.

“These chemicals have been around for over 70 years, but only in the past few has public awareness reached levels of critical concern for the water sector,” according to Greg Goodwin, analyst for Bluefield Research. “They are known as ‘forever chemicals’ because they do not break down and are now making their way into humans by a number of pathways, including drinking water and consumer goods.”

Source: Bluefield Research

Source: Bluefield Research

To date, 1,400 industrial & commercial sites have been identified in 49 states with varying amounts of PFAS contamination. The sites include military facilities, industrial sites, airports, and drinking water facilities. Among these, 223 community water systems that serve populations of +3,000 people in 12 states have tested positive.

Currently, there is no enforceable federal limit on PFAS in drinking water, although states are moving forward with varying approaches to identification, monitoring, and control measures. The burgeoning crisis has led several highly affected U.S. states, such as Michigan and New Jersey, to pursue regulatory limits on PFAS concentrations ahead of a slower-moving federal government to remediate PFAS-contaminated sites.

Source: Bluefield Research

Another key, but more complex, regulatory consideration is the PFAS-laden biosolids discovered at wastewater facilities. Wastewater biosolids, a biproduct of the treatment process, are sometimes recycled and used as fertilizer products for agriculture. At this early stage, tests have shown elevated levels of PFAS in biosolids and select agricultural products (e.g., dairy) that could create a potentially disruptive impact on management practices.

“Land augmentation with biosolid fertilizers has not only become a revenue stream from some utilities, but it has also spawned business models focused on utility biosolid management”, says Goodwin. “Certainly, drinking water is the primary concern, which is also an easier fix with proven technology. All it will take are regulations and capital.”