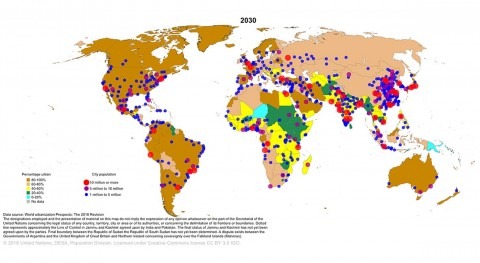

Development in Latin America depends strongly on water. This assertion can be extrapolated across the world, but true enough, a good portion of the largest or more promising economies in Latin America are closely linked to water, such as Mexico, Brazil, Chile, Argentina, or Peru. Whether because they are located in desert or very arid areas, or because of the weight of agriculture in their GDP, or the use of rivers as watercourses, all of them have in common the need to ensure the coverage of drinking water and sanitation services.

The countries in the region have other characteristics common: a natural resource bounty, mostly low population density, a common language and no religious or ethnic conflicts. To that, we can add, for the most part, democracies that are increasingly more consolidated and political maturity, with lower risks. Therefore, here we can say 'Yes, we can': we can achieve sustainable economic growth, a stable, vast middle class, and the status of 'welfare society'.

Appropriate water resource management can be a limiting factor for development. It is not advisable to skimp on resources to preserve water resources and ensure they are used efficiently. This is noted in several reports prepared by multilateral banks, the United Nations or different NGOs working in the region, with the caveat that social inequality is decreasing at a rate that is not proportional to the global growth rate or to wealth generation. Underlying many problems are education, health and drinking water and sanitation services. In fact, the budgets and the programmes continue to increase every year.

A good portion of the largest or more promising economies in Latin America are closely linked to water

This is all well-known: the governments in the region are aware, the large think tanks that support political programmes are aware, academia are aware, the companies such as ours who have flocked to this complex sector are aware, and, most importantly, citizens are aware, even though many cannot articulate it in a global or macroeconomic vision, but their day-to-day is affected by it. But a diagnosis does not lead to change in itself, and big figures do not eradicate problems fast enough.

Let us go back to the factors that threat development and provide an opportunity for change. Should the order of importance not be the opposite? That is, water security leads to effective basic healthcare programmes, and these, in turn, will ensure better quality of life for children, who will be able to attend school and take advantage of the efforts invested in education. If today's objective is eating something nutritious and not lose those nutrients due to acute diarrhoea or chronic parasitism, everything else is secondary. Rural settings in Latin America often share unhealthy conditions, gender violence issues or lack of environmental awareness, regardless of the country or ethnic group involved. And rural populations migrate to large cities looking for opportunities, where they find the same unhealthy and hardship conditions, and in addition rootlessness and vulnerability.

Rural water and sanitation programmes, usually under the responsibility of ministries in charge of housing, regardless of the name, are key to really reduce poverty and inequality, but their effectiveness is questionable. They are questioned by the competent authorities themselves, and sometimes by the responsible managers, middle managers in the public service that lack resources and are not swayed by politicians' promises. We could see different programmes implemented in the same community: a social inclusion programme, a gender programme, a programme on water and sanitation, another one to fight illegal crops, another one focusing on deworming, and yet one more focused on improving children's nutrition. They could be under the responsibility of two, three or four different ministries. There would be no coordination among them to start with, and they would not share economic resources from the same national budget; instead, different ministers would compete for resources. And they would work as isolated initiatives: the people in charge of each programme would not communicate between themselves, neither would the technicians. The latter, concerned about achieving good ratings in the indicators (but not the objectives) and an acceptable ratio (almost impossible) of budget compliance (expenditure committed), do not want to assume or even know about the problems others may have. And yet others may show up with worse intentions, also paid by a public entity, imposing regulations. And for the sake of compliance with rules and processes, sometimes impossible to apply in extreme, remote settings, they would become another challenge for those in charge of programme implementation, at times even paralysing them. And citizens, meanwhile, would be waiting. But everyone has the best of intentions, of course.

Let us look for considerate and creative ways to cover the additional costs involved in providing quality drinking water services in remote areas

This repeats itself within the cycle of project responsibilities. The municipality is usually responsible for water and sanitation, and also population settlements, and overwhelmed with obligations and investment costs, looks for funding in specialised programmes, usually national in scope. When they are successful after a long procedure, so long that sometimes the population served or the quality of the source change in the meantime, they are awarded a construction project (a white elephant sometimes) that they must operate and maintain without any financial support from the institution responsible for the investment. From then on, different solutions are considered, some of them formal, such as associations, boards, etc., that raise just enough revenue to pay for inputs and basic repair and maintenance. Yet in other cases, the infrastructure deteriorates and becomes obsolete way too early. Community-based management by itself does not ensure proper management of infrastructure, provision of inputs and water services according to safety standards.

To the above, we should add a disadvantage: there are some beliefs that are hard to get rid of in Latin America; often they arise from miscellaneous bad experiences in the past. The slogans 'water for the people' and 'water war' or 'no to water privatisation' are popular in many countries and are based on a feeling of ownership of a resource that does belong to everyone; however, to access that resource a service is needed, and the service has a cost. The fact that a proper service has a cost, costs that are accepted for other services, such as a satellite signal or mobile phone coverage even in remote areas of the world, is not accepted in the case of water, and in many places it is an anathema. Why should water services not be under private management? The answer is that it is not fair to pay a certain cost (not a price) for water in very poor communities, or, more so, that the mayor does not want his neighbours to come to his doorstep when he has to cut off the water supply for those that cannot pay for it.

Community-based management by itself does not ensure proper management of infrastructure, provision of inputs and water services according to safety standards

These dead ends in the region have other effects: investment programmes are taken elsewhere or to other sectors and, more critically, a plan B could be accepted. When we talk about a plan B in water and sanitation, it could mean no filters, no disinfection, no trained operators, and therefore no water safety guarantees: we should be appalled. And if this happens in areas with very polluted waters, we would be segregating the population into first and second class citizens. Sometimes it is justified saying that solutions like the ones used in urban areas cannot be taken to complex rural areas such as mangrove areas, the Caribbean, the jungle or the Andes. That is not true: the only water that cannot be rendered potable is the water that does not exist. Electricity arrives late to rural areas, maybe with lower power (equivalent to our peak flow), but it does arrive with a voltage of 110-220 V and a frequency of 50-60 Hz, according to the country. Electrical energy in these areas is not a different energy, nor a plan B energy, even though in this case other resources are available, such as power generators or solar panels. We cannot replace water with soda, especially because in a community in the jungle the price of that soda could be a day's earnings. Water has the same function of ensuring development everywhere in a country. That development is not measured by technology, but by the water safety parameters established to ensure health and guaranteed.

It is necessary to ensure the economic sustainability of the electrical network; in a system of cross-subsidies, the tariffs in urban areas subsidise the additional costs of extending the electric grid to remote areas. Let us look for considerate and creative ways to cover the additional costs involved in providing quality drinking water services in remote areas, but without lowering the requirements, because in a few days without disinfection you can lose the effect of months of safe water.

We should advocate for the coordination and promotion of umbrella programmes with funds from different sectors or ministries, to achieve common objectives as a country, taking advantage of synergies between health and water, or social inclusion and housing. Similarly, let's ensure that management, whether public or private, makes a difference with regards to the improvement and sustainability of drinking water and sewerage services, in rural areas too, incorporating technology and ensuring that operating costs are financed through solutions that, as I mentioned earlier, are considerate and creative, instead of abandoning the investments done.

At INCLAM we have developed initiatives to provide safe water that can be transferred and adapted to places with complex logistics and a scattered population. Residents welcomed such initiatives and we stayed for more than three years to help with the maintenance and operation of equipment. We have provided services with an impact on the development of more than 20,000 people in jungle areas, developing technical competence locally, and we found that — something unusual in that context — people are willing to contribute a co-payment.